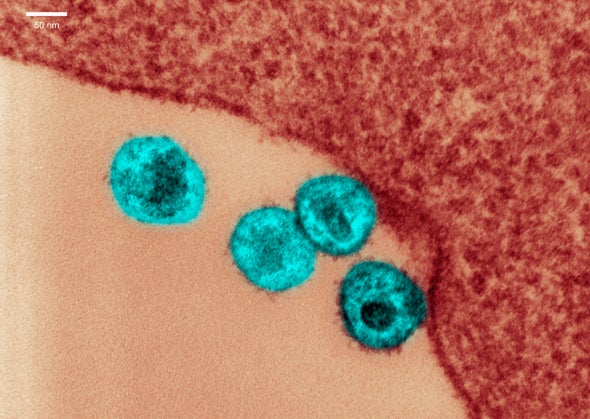

A newborn immune system responds to HIV infection less effectively than a more mature one, so an HIV-positive baby should be started on antiretroviral therapy as soon after birth as possible, new research suggests.

Although treatment early in life was known to be advantageous, the study, published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine, shows the immune system’s response in detail for the first time. The study could energize efforts to treat newborns with HIV, several experts say, and it may help pave the way for an eventual long-lasting treatment or even a cure.

In the study, 10 HIV-positive newborns in Botswana were started on antiretroviral therapy—the gold-standard treatment for HIV—within hours or days of birth instead of the more typical four months. If an HIV-positive pregnant woman is receiving treatment, and the amount of virus in her body is well controlled, she will not pass the disease on to her baby, although the infant will have antibodies to HIV in his or her bloodstream. If the mother’s disease is not well controlled, the baby may be born with HIV.

To look for HIV-positive babies, the team screened more than 10,000 newborns using very small amounts of blood. The researchers identified 40 who were HIV-positive and began treating them with a three-drug cocktail within days of birth. The study reported on 10 of those babies, who are now almost two years old, and compared them with HIV-positive babies who did not receive treatment until four months of age.

The early treated babies fared much better in measures of viral levels in their bloodstream and lower levels of immune activity, which predicts the course of the disease, according to the study, which was conducted by a research team at the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership in Botswana. The babies coped well with the drug regimen, with only one having to discontinue therapy because of side effects, said Roger Shapiro, a senior author of the paper and an immunologist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, in a news conference on Tuesday.

The stakes are high for getting these babies treated, says Pat Flynn, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., who was not involved in the new study. HIV infection can have devastating neurological consequences, likely because of ongoing inflammation in the brain.

Every day, between 300 and 500 babies in sub-Saharan Africa are infected with HIV, according to the study’s authors, who cite data from the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Up to half of them will die by age two if they do not receive antiretroviral therapy. Infants infected in utero face even worse outcomes than those infected during birth or breastfeeding, said Mathias Lichterfeld, a co-author and an infectious disease specialist at the Ragon Institute and Brigham and Women’s in the news conference. Putting all HIV-positive pregnant women on antiretroviral therapy is the best way to prevent them passing the virus to their babies, but many such women face barriers to accessing treatment, Shapiro said.

Scientists have known since a study published in 2008 that treating HIV-positive babies as early as possible leads to better outcomes, but the new paper provides a “very comprehensive scientific rationale for why that is the case,” says Sten Vermund, dean of the Yale School of Public Health and a pediatrician and infectious disease epidemiologist, who was not involved in the new research. “As soon as possible might be too late. We really would be better treating right at birth.”

Compared with the immune system of an older baby or an adult, Vermund says, the newborn immune system is much more immature but “developing at a breakneck pace.” That’s why infants are particularly vulnerable to intrauterine infections, which include toxoplasmosis, rubella, syphilis and Zika. And, he says, “HIV can be added to that list, given the findings of this study.”

Unfortunately, Vermund says, it is unrealistic to think that most HIV-positive babies born in sub-Saharan Africa could be treated soon after birth. “The science is terrific,” he says of the new paper, but it may not have much effect in the real world. “The clinical relevance in Africa is not at all obvious to me,” Vermund adds.

In most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, infants are tested for HIV at four to six weeks of age, Shapiro said in the conference. This practice enables doctors to catch babies who are infected during pregnancy, at delivery or very early in life, but it misses the chance to start treatment immediately if the child is infected at birth. Adding a second test at birth—as South Africa now does—would be complicated and expensive, he conceded, but “that’s really the direction that the rest of the world should be following.”

Yet even something that is simple in the U.S.—such as drawing blood from a newborn, taking the blood to a lab, and getting results back to the clinic and the family—remains “a major barrier to identifying those babies who are infected very early on,” Flynn says. Instead it may make sense to determine women who are at high risk for transmitting HIV and put their infants on therapy even before the test results can be returned. But even then, maintaining stocks of antiretroviral drugs continues to be an issue in sub-Saharan Africa, she says, with funding streams to pay for medications being uncertain.

In the U.S., no more than about 50 babies are born each year to mothers who did not know they were HIV-positive, and they are generally identified at birth, Vermund says. The new study should “stimulate obstetricians and pediatricians to be especially aggressive” in promptly diagnosing and treating those newborns, Vermund says.

The research team plans to follow the babies and track how much viral “reservoir” they continue to carry. In a natural experiment in the U.S., the so-called Mississippi Baby was thought to be cured when her HIV remained undetectable for two years after stopping therapy. But then the disease rebounded, suggesting that early aggressive therapy is not a cure.

To improve long-term treatment of HIV-positive children, the researchers hope to put some of the babies on so-called broadly neutralizing antibodies—which can recognize and block many types of HIV from entering healthy cells. They want to see if, long-term, these antibodies can substitute for the antiretroviral regimen, which is costly and cumbersome and comes with significant side effects.

Yvonne Maldonado, an expert in pediatric infectious diseases and epidemiology at Stanford University, who was not part of the new study, says the real benefit of the new study may not be in how it impacts the care of newborns with HIV but rather in the insights it offers into the HIV reservoirs that remain in the body even during treatment. “This is really geared toward ‘How do you get to the cure?’ rather than ‘How do you treat babies?’” she says.