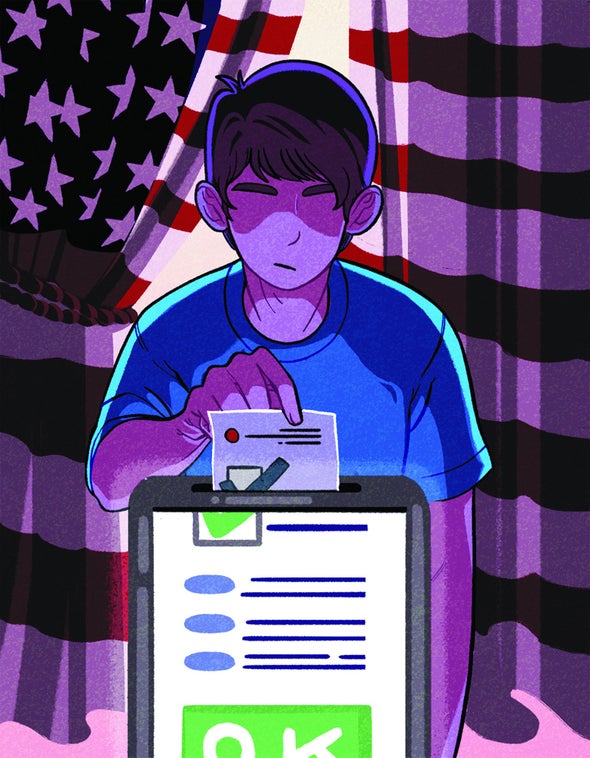

In the run-up to the 2016 U.S. elections, Russian hackers penetrated state voter-registration databases, and Russia's Internet Research Agency targeted millions of social media users with pro-Trump propaganda posts and ads. On Election Day, voting machines malfunctioned in at least nine states. Even now, nearly a whole election cycle later, about a quarter of the states do not insist on voting equipment that generates the paper trails needed for rigorous postelection audits. How can we be sure, then, that the 2020 elections will be fair and tamper-free?

We can't. But one piece of good news is that in September 2019, Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky dropped his opposition to an amendment providing $250 million in new federal spending on election security. The money will go to help state election offices replace outdated voting equipment and improve cybersecurity.

Another positive development is that technologists in the private and nonprofit sectors are tackling the election security challenge at multiple levels. Microsoft, for example, is partnering with Galois, a Portland, Ore.–based firm focused on trustworthy computing, to build a free, open-source software kit for election officials called ElectionGuard. It uses a technique called homomorphic encryption to maintain voter anonymity while allowing anyone to verify that votes have been correctly counted. Similarly, the San Francisco nonprofit VotingWorks is creating free, open-source software that helps jurisdictions run “risk-limiting audits,” which have emerged as the gold standard for efficiently determining whether the outcome of an election was correct.

Soon it may even be possible for everyone to vote easily and securely on their smartphones. I visited a Boston start-up called Voatz whose iOS and Android apps have already been used in three states to allow remote voting by military personnel stationed abroad and people with disabilities. It uses video selfies to verify voters' identities and sends blockchain-encrypted votes to a digital lockbox. On Election Day, officials in the voters' jurisdiction open the lockbox, print corresponding paper ballots (creating an auditable paper trail) and run them through standard optical scanners. “We felt like that was a good step, to show that even a very modern system can integrate with a legacy infrastructure,” says Voatz co-founder and CEO Nimit Sawhney.

The bad news is that none of this technology will be ready for wide deployment in the 2020 election. ElectionGuard is only in the pilot-testing phase, and Voatz's most significant remote-voting project, during West Virginia's 2018 midterm elections, involved only 144 ballots in 24 counties.

And none of these fixes addresses voters' vulnerability to social media–based influence operations. “If I were the Russians, how do I win, if I want Trump to win? I suppress 20,000 African-American votes in Michigan,” says Juliette Kayyem, a counterterrorism scholar at Harvard University, who was an Obama-era assistant secretary in the Department of Homeland Security. “I don't do it the same way I did it before. I'm going to do fake news that there is an active shooter” at a polling place.

Don't expect much help on the disinformation front from the social media giants, which are already dodging responsibility for the ways their platforms could amplify division in 2020. Last September, Facebook said that it won't try to fact-check political speech or ban political ads that make false claims. “How the players play the game is up to them, not us,” said Nick Clegg, Facebook's vice president of global affairs and communications.

In the end, an election is a complex sociotechnical machine, which means all citizens—not just election officials—will need to be on guard in 2020 and beyond. “While we can be very sure that it's really, really hard to alter a vote, it's a lot easier to convince people that something bad happened by just spreading bad information,” Sawhney says. “I think that is the hardest problem to solve.”