“Stop faking!” Imagine hearing those words moments after your doctor diagnosed you with, say, a stroke or a brain tumor. That sounds absurd but for many people diagnosed with a condition called functional neurological disorder (FND), this is exactly what happens.

Although the disorder is not well known to many people, FND is actually one of the most common conditions that neurologists like myself encounter. In it, abnormal brain functioning causes symptoms to appear. FND comes in many forms, with symptoms that can include seizures, feelings of weakness and movement disorders. People may lose consciousness or their ability to move or walk. Or they may experience abnormal tremors or tics. It can be highly disabling and just as costly as structural neurological conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.

[Read more about new findings on functional neurological disorder]

Although men can develop FND, young to middle-aged women receive this diagnosis most frequently. And during the first two years of the COVID pandemic, FND briefly made international headlines when functional tic-like behaviors spread with social media usage, particularly among adolescent girls.

So why would a doctor or other medical professional accuse someone who has lost control of their limbs or has experienced a seizure of faking their symptoms? Unfortunately, many such professionals have a poor or outdated understanding of FND, despite the frequency with which they encounter it. Because nothing is structurally wrong with the brain—there’s no injury noted on clinical testing, for instance—they may write your symptoms off as “all in your head” or dismiss them as psychological. That response, recent research shows, can harm a patient who is already suffering. Fortunately, there is another path forward, rooted in sensitivity, respect and new evidence-based approaches.

Historically, FND was called “conversion disorder.” The term came from the belief that traumatic stress “converted” into functional neurological symptoms via psychological mechanisms. This is no longer how we understand FND. Stress and trauma can play a part. In fact, some researchers believe the unique global stressors our society faced during the COVID pandemic increased some people’s susceptibility to the condition. But not every person with FND has experienced a traumatic event.

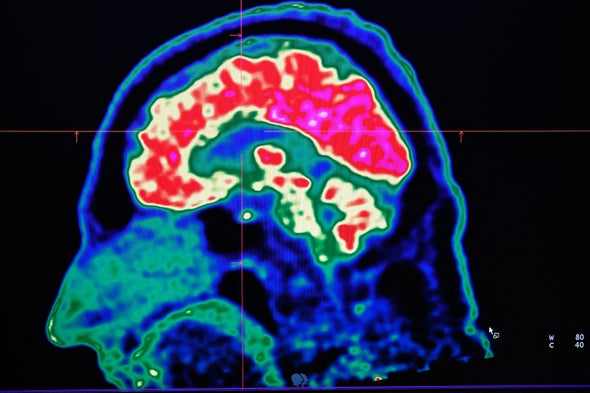

Instead recent advances in brain imaging suggest that FND is caused by abnormalities in the functioning of brain networks. Some experts use the analogy that the brain’s hardware (or structure) is unchanged, but the software (or processing) is malfunctioning. For example, studies suggest that, in FND, the neurological networks—electrical and chemical signaling pathways between groups of neurons or larger brain regions—that affect our reactions to traumatic stress, emotional regulation, sensorimotor functioning, attentional processing, body awareness and self-agency are not functioning together, as is typically expected. These networks include limbic system structures, such as the amygdala, which are important in our brain’s processing of emotions and stress.

Neuroimaging underscores that people are not “faking” anything. Scientists have found decreased activity in areas that influence whether a patient’s symptoms feel under their control. There are also abnormalities in the connections between brain areas responsible for interpreting internal physical sensations and motor planning. Simply put, one of the hallmark features of FND is that patients feel their symptoms are involuntary. By contrast, as a research team at the University of Calgary in Alberta explored in a paper published last November, patients with the structural neurological condition Tourette’s syndrome report some degree of control in suppressing their tics.

Clinicians are also finding better ways to diagnose FND. In the past, neurologists considered conversion disorder to be a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning a diagnosis was made after ruling out structural neurological abnormality through examination, radiological imaging, laboratory studies and neurophysiological testing such as electroencephalography (EEG). As a result, many patients with FND felt their doctor had told them what they didn’t have, not what they did have.

But in the past decade neurologists have developed diagnostic criteria to determine which symptoms are linked to functional brain abnormalities. These emphasize characteristic “positive,” or “rule-in,” findings based on a neurologist’s physical examination, which can predict FND as the basis for a patient’s symptoms. A combination of a thorough neurological examination, EEG, brain imaging and laboratory testing can show whether a person’s symptoms are consistent with a structural brain pathology—for instance, a stroke or a brain tumor—or a functional condition such as FND.

Together, these advances in the diagnosis and understanding of FND mean that doctors are in a better position than ever to identify and understand this disorder. Nevertheless, many patients still have the disorienting, distressing experience of being treated with dismissal or disbelief by medical professionals.

This reaction has damaging consequences. In January a collaboration of researchers at the University of Sheffield in England, Arizona State University and the Northeast Regional Epilepsy Group laid out case studies and other evidence that clinicians’ unsupportive response to their patients may contribute to a sense of shame in people who are already suffering psychologically from their functional symptoms. In fact, being prone to shame may itself be an additional risk factor for FND.

This connection to shame and stigma takes on an even greater weight when we consider that minoritized groups such as LGBTQ+ community members may be at an increased risk for functional disorders. A person experiencing stressors—such as discrimination, bias and stigma—because of their minoritized identity can internalize feelings of shame when their psychosocial support systems and coping mechanisms are inadequate or overwhelmed. If someone in this situation has FND, receiving treatment from a doctor who lacks empathy or a current understanding of the condition only makes things worse. Telling a patient their condition is “in their head” contributes to medical misinformation and further stigmatizes patients with these disorders.

But this problem can be addressed. Researchers have found that how empathetically a doctor informs their patient about an FND diagnosis influences that patient’s likelihood to accept the diagnosis and successfully complete treatment. And appropriate treatment works. Therapy may combine psychoeducation, medication for any coexisting mental health conditions, psychotherapy and physiotherapy. Outcomes for people who receive sensitive and appropriate care are actually very good.

This year my colleagues and I will publish our observations on the treatment of LGBTQ+ people with FND. Our preliminary findings are promising. Most patients had improvement or complete resolution of their functional symptoms following treatment. In some of our patients, these results can be really important. We have treated patients with functional blindness who then regained the ability to see. And we have watched those in wheelchairs regain the ability to walk. In short, care and compassion can be powerful medicine.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about for Mind Matters? Please send suggestions to Scientific American’s Mind Matters editor Daisy Yuhas at pitchmindmatters@gmail.com.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.