As with most things related to people, the food we eat comes with a carbon cost. Soil tillage, crop and livestock transportation, manure management and all the other aspects of global food production generate greenhouse gas emissions to the tune of more than 17 billion metric tons per year, according to a new study published on Monday in Nature Food. Animal-based foods account for 57 percent of those emissions, and plant-based ones make up 29 percent. The researchers hope the paper’s detailed breakdown of how much each agricultural practice, animal product, crop and country contributes to carbon emissions can help focus and fine-tune reduction efforts.

Though previous studies have estimated emissions from agriculture, the authors say this work is more detailed and comprehensive. It uses data on 171 crops and 16 animal products from more than 200 countries, along with computer modeling, to calculate the amounts of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide that are contributed by individual elements of the global food system, including consumption and production. If we want to control those emissions, “we needed to calculate a good baseline,” says study co-author Atul Jain, a climate scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The results align with other research, says Liqing Peng, a food and agriculture modeler at the nonprofit World Resources Institute, which published its own report on agricultural emissions in 2019. The new study’s estimate of total emissions is on the higher side of the range of previous ones, she says. This is partly because it includes data on farmland management practices, such as irrigation and planting, as well as activities beyond the farm, such as processing and packaging—numbers which are difficult to obtain. “It’s really important to get as detailed as possible on these breakdowns” in order to know where to concentrate emissions-reduction research and policies, Peng adds.

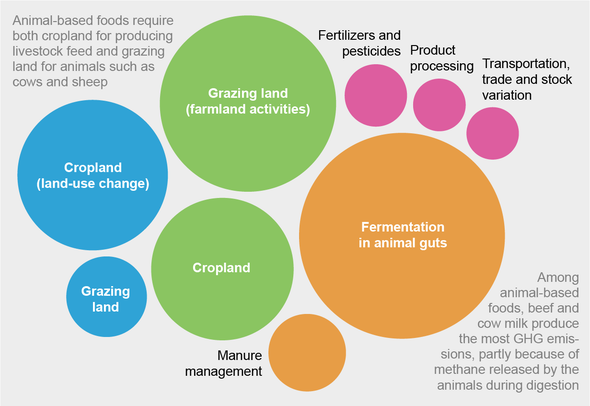

Of the food products the study examined, beef production was the top emissions contributor by a wide margin, accounting for 25 percent of the total. Among animal-based products, it was followed by cow milk, pork and chicken meat, in that order. In the category of crops, rice farming was the top contributor—and it was the second-highest contributor among all products, accounting for 12 percent of the total. Rice’s relatively high ranking comes from the methane-producing bacteria that thrive in the anaerobic conditions of flooded paddies. After rice, the highest emissions associated with plant production came from wheat, sugarcane and maize.

As for contributions from individual regions, South and Southeast Asia comprised the overall top emitter of greenhouse gases related to food production and the only region where plant-based emissions were higher than animal-based ones because of rice cultivation. Among countries, China, India and Indonesia had the highest plant-based food production emissions. This, again, was linked to rice farming, as well as large populations that create a high demand for food—which drives more conversion of land to agricultural production. Because of their large populations, these areas registered relatively low per capita production emissions. The highest per capita emissions (and the second-highest regional emissions overall) were found in South America because of its relatively large production of meat, particularly beef. North America had the second-highest per capita production emissions, followed by Europe.

The study also broke down emissions caused by various aspects of food production and consumption. Farm activities, such as plowing soil or using other types of equipment—along with the conversion of land from forests or other natural landscapes into pasture and cropland—collectively accounted for two thirds of emissions.

Jain and his colleagues want to use these results, along with computer modeling, to examine how changing farmland management (reducing fertilizer use or employing no-till soil methods, for example) could reduce emissions. They also want to study how to balance the food requirements of a growing global population with the need to halt deforestation. “That’s why we put so much effort” into being so comprehensive in the new paper’s accounting, Jain says. His co-author Xiaoming Xu, also at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is optimistic about the prospects of making a dent in food-based emissions. “I think there are a lot of options we can do,” he says. But Peng notes that meeting the current—and ambitious—international emissions-reduction targets will mean figuring out which approaches not only make the most economic sense but also provide the biggest bang for the buck in terms of getting results. “You want to do everything,” she says, “but you can’t do everything at the same time.”