More than 270 million registered cars, trucks and buses currently drive along on U.S. roads, or about one for every U.S. resident aged 15 or older. Transportation is the leading source of greenhouse gas emissions in the country—and accounts for 15 percent of emissions globally. So transforming the way we get around is a crucial part of the effort to tackle the climate crisis.

People and governments have recently been taking some encouragingly concrete steps in this direction with projects related to transit and city planning. They provide a basic blueprint for bringing down emissions and other vehicle-created pollution. Here Scientific American takes a look at three examples that range from simple to high-tech.

Bike Buses

In 2021 children in Barcelona started bicycling to and from school together with the help of adult volunteers in a group that has been termed a bicibús, or “bike bus.” According to Reuters, an estimated 700 people joined bike bus routes in the city in the 2020–2021 school year. In the following year 14 more routes were added in Barcelona. Other cities have also jumped on the bike bandwagon, with similar convoys popping up in Hamburg, Germany, Glasgow, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Boulder, Colo., Chicago, Brooklyn, N.Y., Arlington, Va., and Portland, Ore.

More children biking to school rather than riding in fossil-fuel-powered school buses or cars could be a small step in reducing transportation-related emissions.

Some researchers say increased bicycling not only cuts emissions but could also help assuage children’s climate anxiety. Carlie Trott, a social psychologist at the University of Cincinnati, says small acts of everyday activism—such as cycling or planting community gardens—can help young people feel less anxious about climate change and more empowered to confront it.

Trott has been studying the impact of such activism on 10- to 12-year-olds. She was frustrated with the lack of much existing research on how climate change affects young children psychologically. “What I found was that ... doing some of the day-to-day lifestyle behaviors actually has these psychological benefits,” she says. “That was meaningful because they’re developing the sense that they’re able to make choices and do things that are within their own sphere of influence—which can be limited the younger you are.”

Open Streets

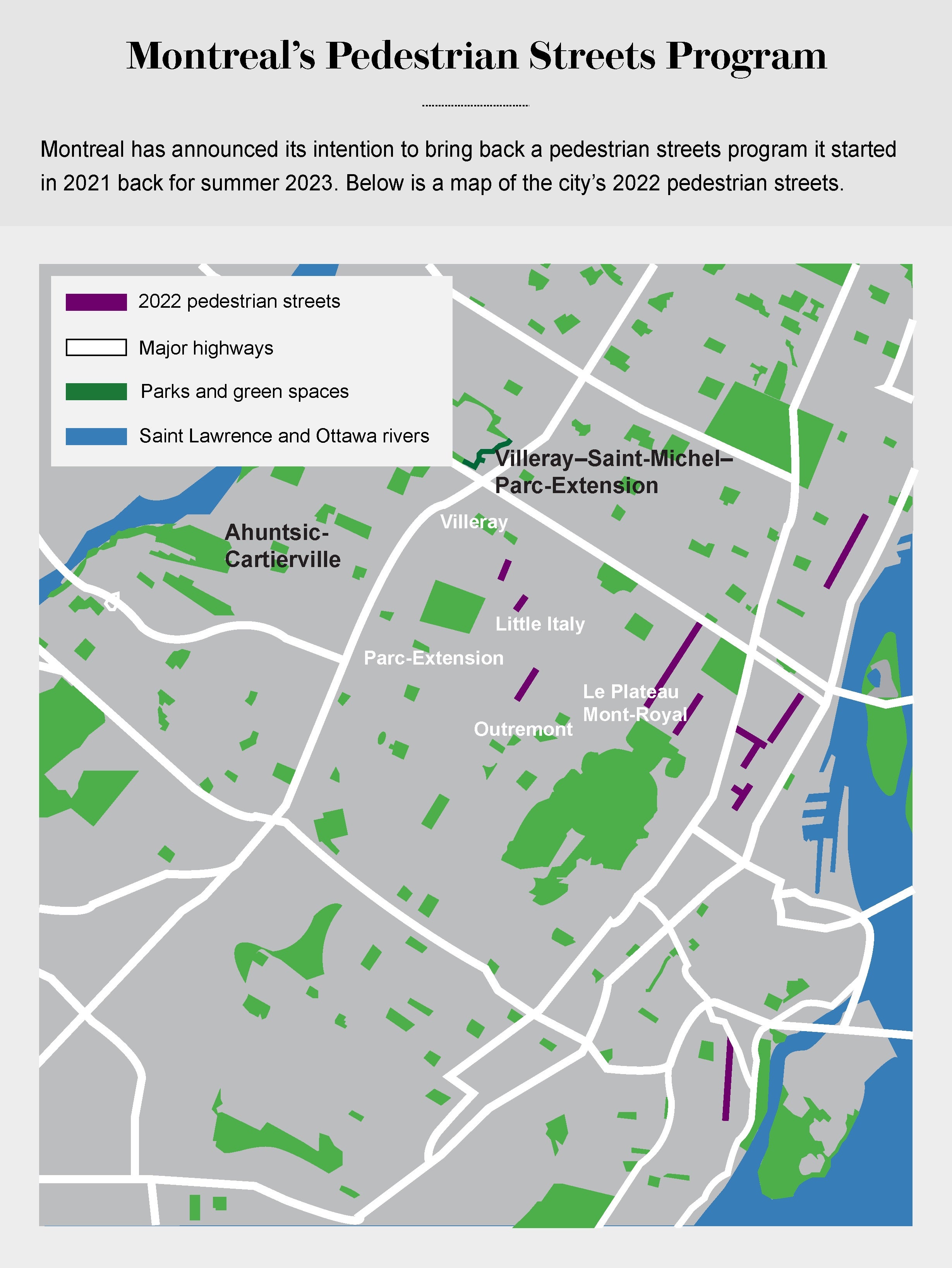

During the COVID pandemic, the dearth of safe places to congregate indoors led many cities across the world to start “open streets” programs. Also dubbed “slow streets,” “safe streets” and “shared streets,” the idea involves “pedestrianizing” streets by limiting vehicle traffic to allow more people to safely walk or cycle in cities. In 2022 these programs popped up or expanded in New York City, Boston, Bristol, England, Montreal and Shanghai, among other cities.

Epidemiologists at the Barcelona Institute of Global Health and the University of Leeds in England concluded that restricting private cars in city centers may help reduce premature mortality by improving air quality and increasing opportunities for physical activity. And researchers at the Institute of Urban Transport India have argued that pedestrianization can also decrease noise pollution and fuel usage for city dwellers.

In 2021 Javier Borge-Holthoefer, research director of the Interdisciplinary Internet Institute at the Open University of Catalonia in Spain, was inspired by the growth of Open Streets programs—and decided to study how to optimize them. He and his colleagues used a so-called network analysis, a process that looks at how different people or objects relate to and interact with one another. The researchers employed this technique to measure cities’ sidewalk network connectivity and identify places where cities could improve sidewalk networks while preserving vehicle mobility.

They found that by pedestrianizing key streets with wide sidewalks, New York City and Paris could connect more sidewalks without adding much to the lengths of drivers’ trips. Similar interventions in Boston and Montreal would more substantially affect trip times, however, suggesting more research is needed on how to make the idea work in different cities.

As pandemic restrictions have eased, some cities have cut back on these programs—so their future is still uncertain. “There’s this kind of uneven attitude,” Borge-Holthoefer says. “Some cities are going back to the old style of urbanism, [but] some of them have really realized that they can bring a very positive change.”

Electric Vehicles

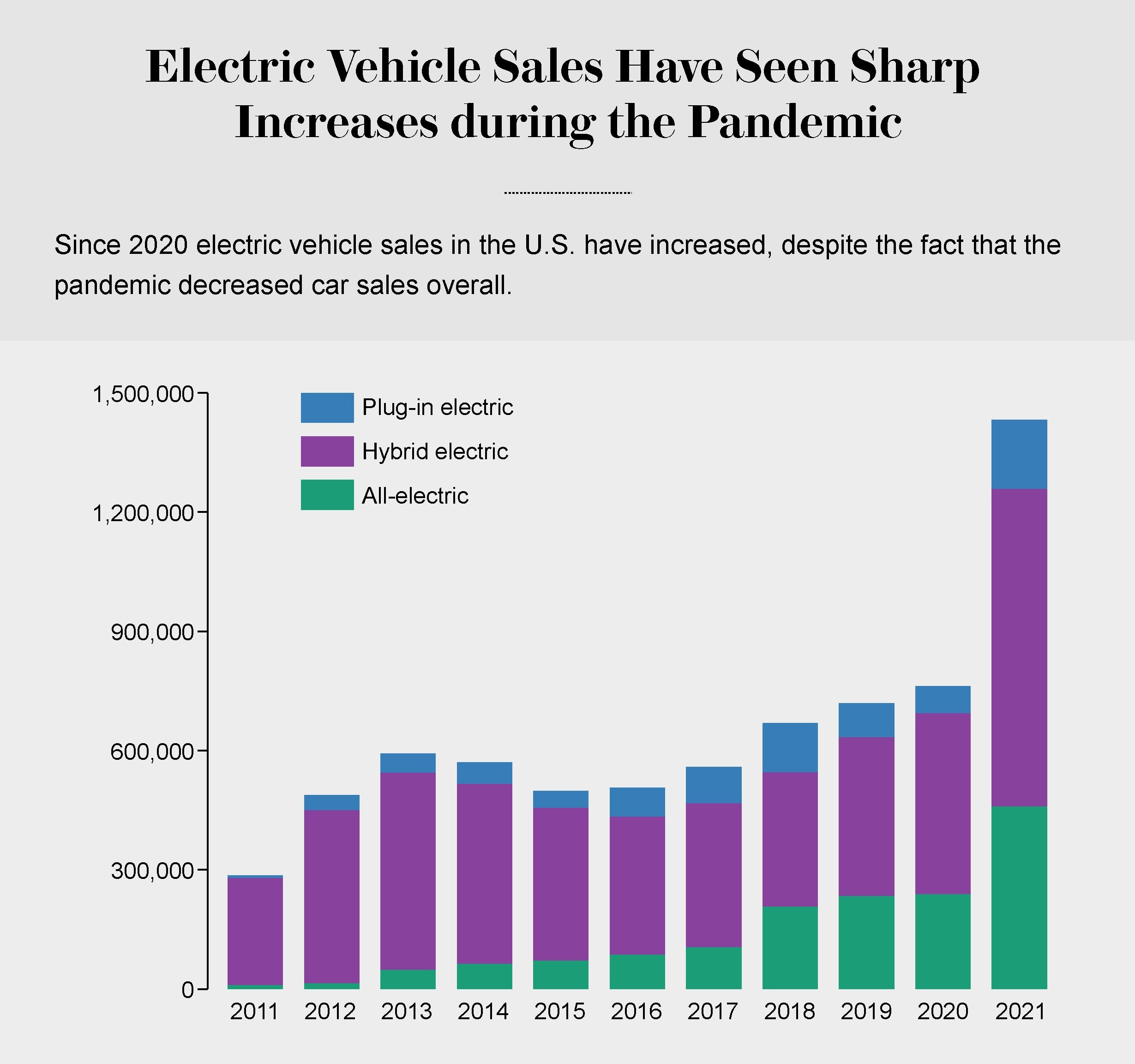

Electric vehicle sales are another transportation sector in which significant strides have been made.

According to EV-Volumes, a database of such sales, 62 percent more electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids were sold in the first half of 2022 than in the first half of 2021, even as overall car sales remained down because of the pandemic. In the U.S. electric vehicle purchases could account for 67 percent of the country’s car sales by 2032 if the Environmental Protection Agency passes its recently proposed rules on automotive pollution.

Switching to electric vehicles not only reduces planet-warming emissions from the transportation sector but also lowers other air pollutants that are produced by fossil-fuel combustion and harmful to human health—and that disproportionately affect people of color and poorer communities. “Getting rid of the combustion gasses from vehicles has huge, huge public benefit now,” says David Wooley, executive director of the Center for Environmental Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. “Even if you’re not really concerned about climate, almost everybody wants to improve air quality for public health.”

Switching countries’ entire car fleets to electric vehicles does pose potential problems, such as causing possible shortages of the lithium needed to make car batteries. Additionally, electric vehicles are only as clean as the electric systems they draw power from. In areas where coal is still the main fuel at power plants, for example, these vehicles may not improve greenhouse gas emissions.

But there is promise for solving some of the issues that mass electric vehicle adoption could cause. Scaling up renewable energy will be one crucial element. The 2022 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in the U.S. has put more money into increasing the country’s battery recycling capacity, which could mitigate the potential for lithium shortages, Wooley says.

Wooley co-authored an April 2021 U.C. Berkeley report on transportation that examined how the U.S. could get 90 percent of its energy from clean sources by 2035. He is confident that by 2050, almost all vehicles, including heavy-duty ones, will run on electricity or other zero-carbon fuels.