More than a century of burning fossil fuels has unleashed fiercer heat waves and droughts, heavier downpours that cause massive floods and other extreme climate disruptions. If we want to avoid even worse effects of climate change in the future, humans need to keep the rise in global temperatures as far below two degrees Celsius as possible. To meet that target, we can only emit a certain amount of additional carbon dioxide. This is called the world’s “carbon budget.”

As with a financial budget, if we “overspend” by emitting more CO2 than our budget allows, we go into “carbon debt”—and also confront more extreme climate impacts that will be harder and costlier to adapt to. And we are currently on course to significantly overspend. Global temperatures are already a little more than one degree C warmer now than in preindustrial times.

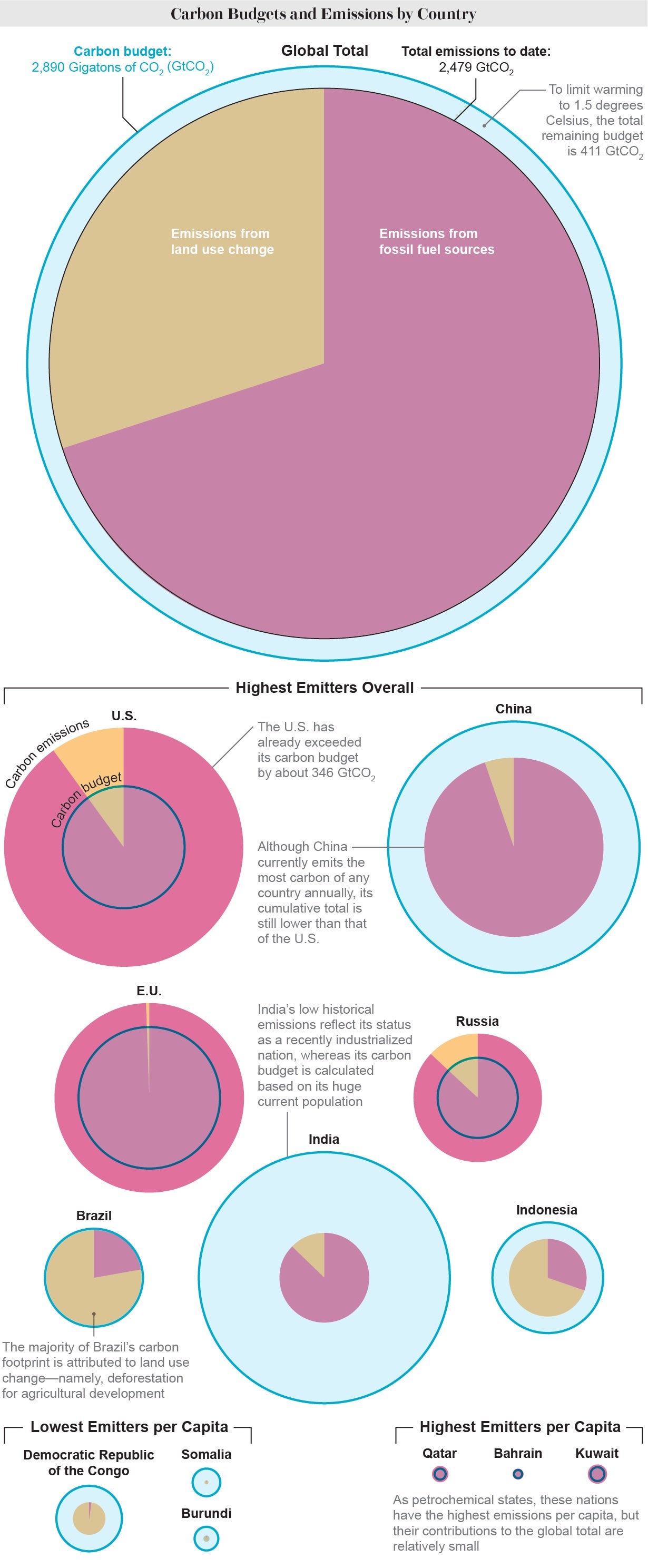

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) calculated that between 1850 and 2019, we emitted about four fifths of the amount of CO2 that would give us a 50–50 chance of keeping the world’s temperatures from rising by more than 1.5 degrees C since preindustrial times (the highly ambitious goal agreed to under the 2015 Paris climate accord). To maintain that 50–50 chance, we could only emit about 500 more gigatons of carbon dioxide between 2020 and 2030, the IPCC calculated. This carbon budget does not include other greenhouse gases or the cooling effect of aerosols, among other factors. But given that carbon dioxide is the most prevalent greenhouse gas, the budget still provides a good sense of how much more can be emitted. If we want higher odds of staying on target, our carbon budget will have to be lowered.

This is a tall order, considering that the world is currently producing about 40 gigatons of CO2 per year and that global carbon dioxide emissions are still rising, meaning we will exceed the 50–50 budget in about a decade. This collision course with climate catastrophe is why the IPCC report also called for fast, deep emission cuts to limit temperature rise as much as possible. “We do not have much wiggle room left at all,” says climate scientist Kirsten Zickfeld of Simon Fraser University in British Columbia.

Politics and entrenched economic interests make such emissions cuts difficult to pull off. Also complicating international negotiations on climate action is the issue of equity: the world’s countries have not contributed equally to the climate crisis—and this disparity can be seen in stark clarity by breaking down the carbon budget at the national level.

Scientific American analyzed the national carbon budget of a select group of countries by adding total historical emissions (including both fossil-fuel burning and land-use changes such as deforestation) to the estimated remaining budget needed for a 50–50 shot at limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C. That number was divided by the total world population to determine a per-person carbon budget, which was then multiplied by each country’s population to get that nation’s total budget. Each country’s budget is compared with its historical emissions in the graphic below. Because of various uncertainties in any calculation of the carbon budget, the exact numbers in the graphic are much less important than the overall disparities among countries.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Sources: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, 2021 (carbon budget); Supplemental Data of the Global Carbon Budget 2022. Global Carbon Project, 2022 (emissions data); World Bank (country populations and per capita emissions data); Data analysis by Amanda Montañez and Piers Forster

It is clear that nations such as the U.S. and Russia, as well as the collective European Union, have blown past their fair share of the carbon budget. Conversely, countries that have industrialized much more recently, such as India, or minimally, such as Somalia, have not come close to using up what would be their fair share of the budget. “It highlights a moral position,” says Joeri Rogelj, a climate scientist and director of research at the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London. “It highlights that imbalance that needs to be resolved.”

Though China has also industrialized relatively recently, it is quickly catching up to other industrialized countries and is close to using up its budget. China is now the highest emitter in the world, though it still produces fewer emissions on a per capita basis than the U.S.—which remains the biggest emitter historically.

Based on the dramatic imbalances among countries in causing the climate crisis, India and some other industrializing and developing nations argue they should be allowed to use their fair share of the carbon budget as they grow their economy. “As an independent academic from India, I can say that economic development, an increase in incomes and well-being of its population—a majority of whom lack access to amenities that those in the developed world take for granted—has to be the first priority,” says Tejal Kanitkar, a climate scientist at the National Institute for Advanced Studies in India. “Being a large economy, India has been cognizant that it has to contribute its fair share to the global mitigation effort despite its lack of contribution to historical emissions.”

If India uses up its remaining carbon budget, this would push the world far past its collective climate goals. “You’re sort of entitled to it, but you can’t burn it for the sake of the Earth,” says climate scientist and IPCC author Piers Forster of the University of Leeds in England. India has domestic policies aimed at boosting renewable energy. If successful, these could easily keep the country below the emission limits it set under the Paris Agreement, but India’s coal production and consumption levels are also still rising.

It is also unrealistic to expect the U.S. and other countries in carbon debt to simply turn off emissions tomorrow. But it is still clear that “we’re responsible for most of the warming that is happening and that will occur in the future,” Zickfeld says. “This implies that in terms of mitigation, we should shoulder a heavier burden.”

Developed countries such as the U.S. need to make deeper emission reductions than they have committed to under the Paris Agreement in order to limit temperature rise and reach net-zero emissions by midcentury, climate scientists say. “So far developed countries have made inadequate efforts at reducing emissions and focused their energies on transitioning from one fossil fuel (coal) to another (natural gas), with barely any efforts at shifting oil consumption,” Kanitkar says. “This means that they have used more and more of the [global] carbon budget, leaving very little for developing countries.” And even if developed countries were to somehow reach net zero earlier, “they would still owe a carbon debt to the developing world,” she adds.

Developed countries should consider going further than the midcentury goals, Rogelj says. “Reaching net zero is only the beginning. It’s a milestone and an important one, but there is no reason why we should stop at net zero,” he says. “There’s no significant challenge in going net negative if we meet net zero,” and doing so could provide developing countries with some breathing room to reduce emissions at a slower pace—or, if those countries can also quickly reduce their emissions, it could further limit overall temperature rise.

In addition to reducing emissions as quickly as possible, the U.S. and other developed countries could share their clean energy technology knowledge with developing countries and provide them with funding to create clean energy systems. India has set decarbonization goals that have “serious attendant costs,” Kanitkar says. “India, like many other developing countries, also has competing priorities of development, and this makes the task even more challenging. The requirement of finance, not loans, to meet these goals is therefore important in meeting these pledges.”

Compensation for the irreversible climate damage already done is another area where developed countries can step up. Contentious negotiations on setting up a mechanism for such compensation—known in United Nations parlance as “loss and damages”—are currently underway by a U.N.-created committee ahead of the next international climate summit in Dubai in November. But as with efforts to rein in emissions, getting countries to commit to these actions requires a level of political will that can be extremely difficult to muster.

The urgency to do so is rising as what little budget that remains is being steadily chipped away. “With every year that not only that our emissions don’t decrease, but they actually increase,” Zickfeld says, “that leeway is being reduced.”