Sharks are some of the world’s most formidable predators, but their place at the top of the marine food chain may be threatened by ocean warming and acidification. As carbon dioxide levels in the oceans increase, upping the acidity of the water, shark teeth and scales may begin to corrode, compromising their ability to swim, hunt and feed, according to research published today in Scientific Reports.

Ultimately, sharks could be displaced as apex predators, disrupting entire ocean food webs, says the study’s senior author Lutz Auerswald, a fisheries biologist at Stellenbosch University in South Africa and the nation’s Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. “Some of the bigger species, like great white sharks, are also already highly endangered, so this might wipe them out.”

Auerswald and Sarika Singh, an ocean researcher at South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs, stumbled upon the idea for their study over beers. Realizing that the high acidity of beer and many other carbonated beverages causes human teeth to erode, Singh wondered what effect more acidic ocean water might have on shark teeth.

Most studies on ocean acidification examine species that build shells or other calcium-based structures, including corals and shellfish. Possibly because sharks are large and difficult to work with—and because many of them are endangered—only a few studies to date have looked at how acidification might impact the animals. Just one paper has examined the effect of pH (the scale that measures how basic or acidic a substance is) on sharks’ skin denticles, or scales. That study, conducted on small-spotted cat sharks, a species in the North Atlantic, did not find a significant impact. But its results were possibly constrained by the relatively low carbon dioxide concentration the researchers used, compared with the high levels of acidity already present in many places in the world’s oceans.

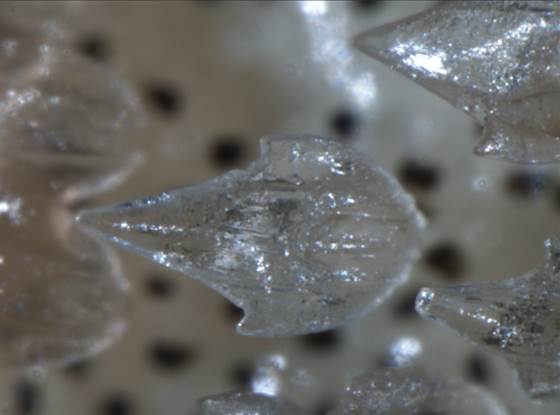

Auerswald, Singh and their colleagues focused on puff adder shy sharks, a small, bottom-dwelling South African species of cat shark that is easily handled and not endangered. The sharks’ teeth are very small, so the team decided to investigate acidification’s effects on the animals’ comparatively bigger scales. (Because shark teeth and scales are both made of a calcium phosphate material called dentin, the researchers would expect the effects on teeth to be similar to any impact on the scales.)

The researchers captured puff adder shy sharks in a harbor in Cape Town, South Africa, and transported them to a government research aquarium, where the fish acclimated for four months. They divided 13 of the sharks into control and experimental groups. Control animals stayed in an aquarium with a mildly basic pH of 8.1, matching that of the ocean, while the researchers gradually dropped the pH of the experimental animals’ water to 7.3, the level that ocean water is predicted to hit by 2300 if carbon dioxide emissions continue. (In some areas, including the waters off South Africa and California, the pH can already drop to 7.3 or lower, depending on prevailing currents and winds.)

After two months, an electron-microscope analysis revealed that the concentrations of calcium and phosphate in the sharks’ denticles were significantly reduced. About 25 percent of the experimental group’s scales were damaged, compared with only 9 percent in the control group. “If dissolution is already visible [after just two months], one can only speculate how the sharks would look after a year or more,” says Fredrik Jutfelt, a biologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, who was not involved in the latest research but co-authored the only other study of shark scales in acidic conditions. “Increased dissolution of denticles could have serious consequences for sharks for many reasons.”

The impacts, however, would likely vary between species, Auerswald says. Puff adder shy sharks are sedentary predators that ambush their prey, so corroded scales might not impact their ability to hunt. But for larger species that swim in open water, such as great white sharks, scales play an important role in hydrodynamics. One study found that shark denticles are responsible for an up to 12 percent increase in swimming speed. Thus, damaged denticles could slow sharks down and make it more difficult for them to catch prey. Scales also protect females from male biting during courtship and help some shark species defend against other predators. Likewise corrosion to teeth could hit some species harder than others.

Other groups of calcifying organisms, for whom the effects of acidification are more well-studied, show these wide-ranging differences. Auerswald and his colleagues have observed that lobsters are quite resilient in the face of acidification, whereas abalones grow significantly slower, and “their shells look horrible,” he says. “A lot of animals have survived even more acidic conditions in the ancient past, but we also know that a lot of species were wiped out,” Auerswald says. “One lesson is that you have to test species by species.”