More than half a century ago, conservationist Rachel Carson sounded an alarm about human impacts on the natural world with her book Silent Spring. Its title alluded to the loss of twittering birds from natural habitats because of indiscriminate pesticide use, and the treatise spawned the modern conservation movement. But new research published Thursday in Science shows bird populations have continued to plummet in the past five decades, dropping by nearly three billion across North America—an overall decline of 29 percent from 1970.

Ken Rosenberg, the study’s lead author and a senior scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the nonprofit American Bird Conservancy, says the magnitude of the decline could significantly affect the continent’s food webs and ecosystems. “We’re talking about pest control, we’re talking about pollination [and] seed dispersal,” he says, referring to the roles birds play in ecosystems. Because it is relatively easy to monitor birds, he adds, their presence or absence in a habitat can be a useful indicator of other environmental trends. Based on the paper’s results, he says, “we can be pretty sure that other parts of the ecosystem are also in decline and degradation.”

Rosenberg and his colleagues used data from citizen-science bird-population assessments, including the North American Breeding Bird Survey and the Audubon Christmas Bird Count, to estimate changes since 1970. In these yearly projects, thousands of volunteers perform “point counts,” tallying all the birds they can see and hear in a short time period at locations along designated routes. This method “is the gold standard in the field of ornithology to survey birds,” says Valerie Steen, an ecologist at the University of Rhode Island, who was not involved in the new study. The researchers say that because they estimated losses only in breeding populations, their results are conservative—meaning total bird losses could be even higher than they reported.

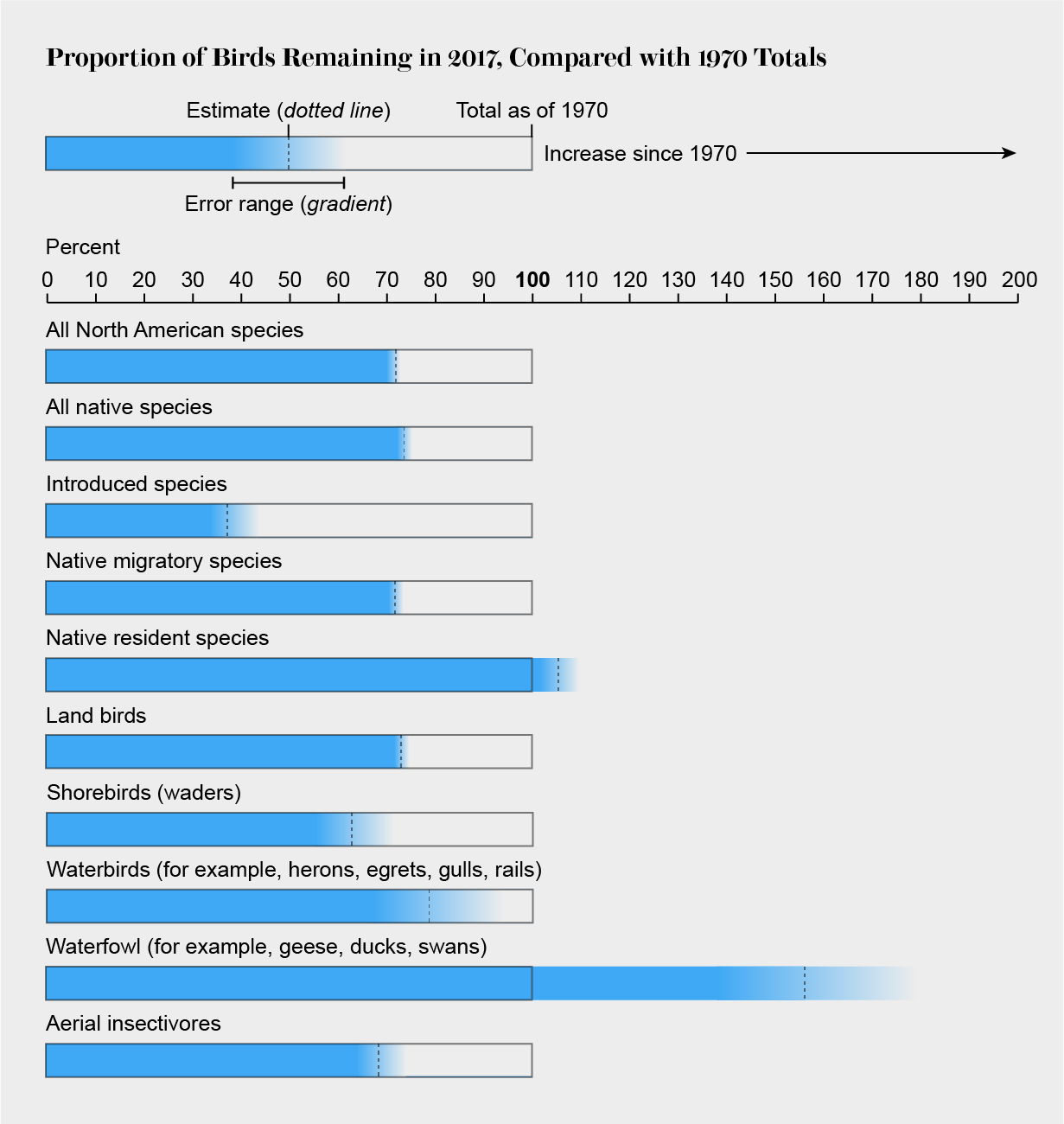

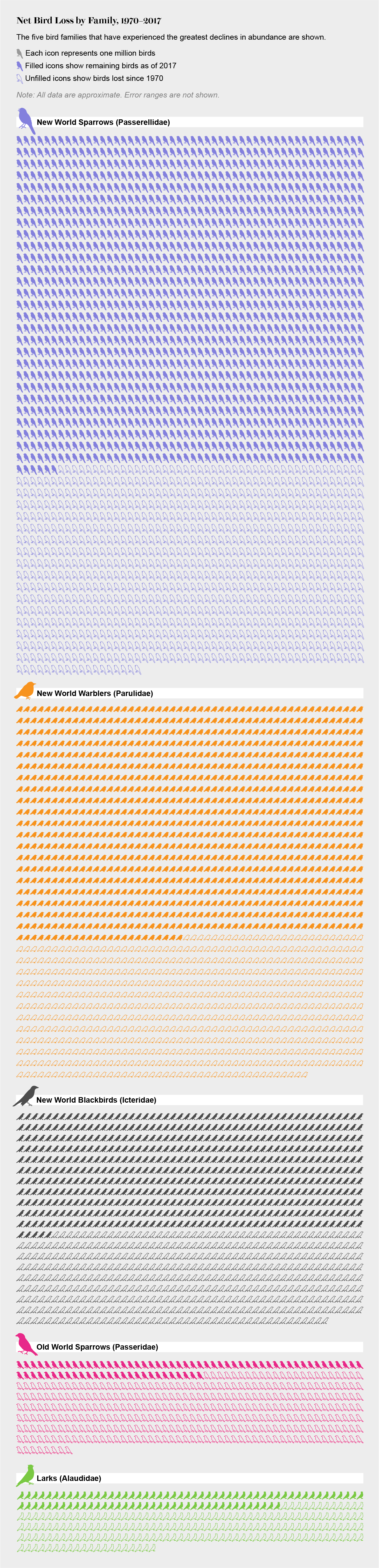

Grassland-dwelling birds such as sparrows and meadowlarks have been hit especially hard. According to the study, more than 700 million birds across 31 species that make their homes in fields and farmlands have vanished since 1970. Rosenberg says the most likely explanation involves changing agricultural practices. “The intensification of agriculture is happening all over the world, [as is] increased use of pesticides, as well as the continued conversion of the remaining grass and pastureland—and even native prairie” to cropland, he says. These changes impact grassland birds in myriad ways: Widely used pesticides kill insects that some birds rely on for food, and exposure to these chemicals can even delay migration. Converting land for agricultural use removes nesting habitat. Shorebirds—which nest in areas particularly susceptible to development and climate change and whose numbers were already dangerously low in 1970—have declined by more than a third.

The researchers also used data from 143 weather radar stations to estimate changes in the total biomass of migratory birds each year between 2007 and 2017. They found similar declines to what the data from volunteer counts showed, particularly along the U.S. East Coast. The survey and radar data “measure different things, but they come to the same conclusion,” says study co-author Adriaan Dokter, a migration ecologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The Atlantic Coast is an important migratory route for warblers, thrushes, spoonbills and many other birds that breed in North America and spend the winter in the Caribbean or in Central or South America, says wildlife biologist and head of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center T. Scott Sillett, who advised the researchers but was not involved in the work. “A lot of migratory habitat for shorebirds and wintering habitat has been lost,” Sillett says. “This study points out that we have a lot more work to do in terms of habitat protection.”

One bright spot the researchers found was that wetland birds have made recoveries, driven largely by increases among waterfowl such as ducks, geese and swans. “It’s because of the strong constituency of recreational waterfowl hunters who raised their voice, put money where their mouths are and saw to it that conservation programs and policies were put in place,” Rosenberg says. “Billions of dollars [were] invested into wetlands [and] into wildlife refuges. The North American Wetlands Conservation Act was enacted in the late 1980s. All of these things were responsible for the turnaround.” The study also found that raptors such as bald eagles have rebounded after legislation extended protections for these birds and banned the pesticide DDT—thanks in part to Silent Spring.

Sillett says that birders and bird enthusiasts could learn from hunters’ conservation efforts. “The rest of us who enjoy birds that are not game species, we’ve got to think of ways that we can contribute to their conservation,” such as taxing hiking or bird-watching equipment to support conservation programs, he says. “I think we all need to throw in a bit and think about how we can come up with a broader model of conserving our wildlife that’s patterned after the waterfowl program.”