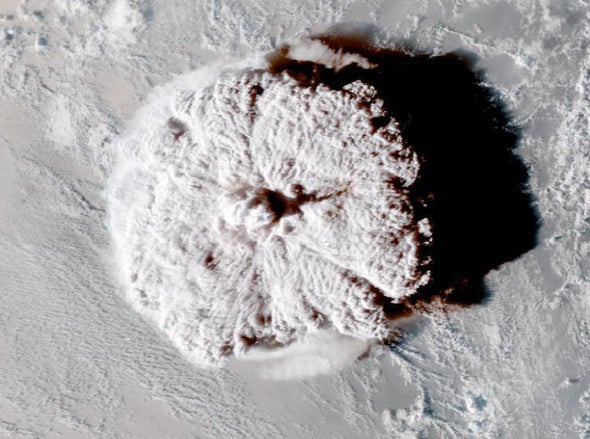

The undersea cable connecting Tonga to the global Internet and phone systems was finally restored in late February. The archipelagic nation’s access had been cut off since January 15, when the largely submerged Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai volcano unleashed a gargantuan blast and tsunami. Powerful underwater currents, perhaps triggered by the volcano’s partial collapse, severely damaged a 50-mile stretch of the 510-mile-long undersea cable that linked Tonga to the rest of the world.

Parts of the government-owned cable were cut into pieces, while other sections were blasted several miles away or buried in silt. This left most of Tonga’s 105,000 residents isolated (aside from a handful of satellite-linked devices called “Chatty Beetles” that could transmit text-based alerts and messages). When it became clear this would last more than a month, a controversial figure stepped in: In late January Elon Musk, billionaire CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, tweeted, “Could people from Tonga let us know if it is important for SpaceX to send over Starlink terminals?” Musk’s offer of this satellite Internet connectivity equipment appeared to be well-received by Tongans reeling from the disaster. Almost immediately, the company flew a team of its engineers to the remote Pacific islands.

At a glance, providing the stricken country with another way to access the Internet in the longer term—aside from a vulnerable undersea cable—seems like a helpful development. And it is not the only occasion when Starlink has offered its service in the wake of disaster or disruption. In 2020 the company also sent Washington State seven terminals, small dish antennas that communicate with Starlink satellites in orbit, to use during wildfire season for free. This gave besieged residents and emergency responders vital Internet access, says Steven Friederich, a public information officer at the Washington Military Department. And on February 26 Musk said on Twitter that Starlink service is now active in war-torn Ukraine. (Specific details about the company’s work in the region remain somewhat scarce, but Starlink terminals have been delivered to the nation, and civilians on the ground are reporting that the Internet service is operational.)

Like SpaceX’s other interventions, the offer of Starlink services to postdisaster Tonga certainly has an altruistic element to it. But as other coverage has noted, providing Starlink Internet access to Ukraine is not as straightforward as it seems, and doing so will not end the country’s connectivity issues in the middle of a fight for its survival. For different reasons, SpaceX’s offer to Tonga is also not without complications. Adding another way to access the Internet in the event of a future disaster is obviously welcome. But the decision also benefits the company by helping it move into a new (and vulnerable) market, all while giving Starlink—whose highly reflective satellites have angered many astronomers, among others—a decent public relations boost.

When it comes to Tonga, the awkward mixture of Starlink pros and cons has made some observers wary. “They’re not a charity. They’re not doing this out of the goodness of their hearts,” says Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at University of Regina in Saskatchewan, who has spent the past few years closely monitoring Starlink’s proliferation. “They’re doing this for profit.” (At press time, SpaceX has not responded to requests for comment.)

Given the historical vulnerability of Tonga’s undersea cable (in 2019 a ship’s anchor damaged it and briefly cut off Internet access), a dedicated connection using satellites sounds like a great fit. And Starlink is not the only satellite Internet provider moving into the region. About two weeks after the eruption damaged the undersea cable, Tongan authorities cleared Kacific, a Singapore-based broadband satellite operator, to offer its own services to the country, and it is now starting to roll them out to customers. This type of system works a little differently than Starlink: A customer’s small dish antenna listens to and talks with the geostationary Kacific1 satellite. Kacific1, in turn, communicates with one of three ground stations, or “teleports”—larger dishes located in Australia, Indonesia and the Philippines. A customer’s Internet connection works so long as the Kacific1 satellite can “see” one of these three ground stations and the customer’s own dish. As this satellite hangs out at a very high altitude (about 22,400 miles), pretty much anyone with a dish in the Asia-Pacific region is within range.

Geostationary satellites such as Kacific’s generally offer a slower Internet connection, compared with the low-altitude orbits used by Starlink, however. The latter’s system relies on a ground station called a “gateway,” which is physically wired into the nearest data center or router connected to the global Internet via underground fiber-optic cables. This gateway then beams Internet data from the rest of the world to Starlink satellites, which send the information to small individual dishes, or terminals, on people’s properties. After the recent eruption damaged Tonga’s undersea cable, the country lost its ground-based Internet access—so a gateway could not be set up in Tonga itself. Instead SpaceX chose nearby Fiji as the spot to build a temporary gateway, says Ulrich Speidel, a computer science and data communications specialist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. Last month Fiji’s communications minister Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum announced on Twitter that a “SpaceX team is now in Fiji establishing a Starlink Gateway station to reconnect Tonga to the world.” But little else seems to be known about SpaceX’s efforts. “We had received information from Starlink a few weeks ago regarding their attempt to provide Internet connectivity to the country via Fiji, but so far there’s no development on that. Starlink has been silent since then, and I don’t know why,” says an engineer at Tonga Cable, who wishes to remain anonymous. (At the time of this writing, Sayed-Khaiyum’s office has not responded to requests for comment.)

Fiji may not be an ideal location for the gateway serving Tonga because Starlink satellites in lower orbits cannot receive Internet data from a very distant ground station, Speidel explains, only from one within their relatively restricted view. It has previously been reported that to use Starlink, one’s antenna must be within 500 miles of a ground station. But Speidel says people usually have to be closer—within 180 to 250 miles—to get a high-quality Internet connection. And the new gateway in Fiji is about 500 miles away from Tonga. Speidel notes that future Starlink satellites will use lasers to relay Internet data among one another, meaning they will not all need connections to nearby ground stations in the years to come. But for now, because of this gateway’s distance from Tonga, it remains unclear how effective the Fiji gateway will be for Tonga’s people. As Musk tweeted on February 25, “Starlink is a little patchy to Tonga right now, but will improve dramatically as laser inter-satellite links activate.”

More generally, various satellite Internet systems share similar vulnerabilities. For example, volcanic ash—a layer of which blanketed parts of Tonga following the latest eruption—can cover up and damage satellite dishes. Solar activity can knock out satellites in orbit. “Even if we got every household in Tonga a Starlink terminal, we still have to plan for outages,” says Ilan Kelman, a researcher at the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction at University College London.

Satellite access is also slower and often more expensive than cable Internet, notes Nicole Starosielski, an associate professor of media, culture and communication at New York University. “Most places in the world wouldn’t use satellites if they had access to a cable,” she says. Cables may be vulnerable to damage but can usually be repaired relatively quickly. (In Tonga’s case, a fix was delayed because the nearest cable repair ship was moored in Papua New Guinea’s Port Moresby, nearly 2,500 miles away, when disaster struck.) Regardless, “once they fix the cable, it will be as good as new. They do a really good job with repairing cables,” Starosielski says. Instead of backing up the original cable with Starlink, she recommends supporting it with another undersea cable laid down along a different route, which is “the norm for most parts of the world.”

But a second undersea cable would be a costly option for Tonga—and could still be disrupted. “Even with the backup cable, I’m in no doubt that satellite-based Internet is a must-have at all times, given our geographical position is highly vulnerable to volcanic activities,” says the Tonga Cable engineer. Of all the satellite options, he thinks Starlink would be best, “if they’re willing to help with the costs of expensive satellite capacity and subscription.”

Things are off to a generous start—regional news has reported that 50 Starlink satellite terminals have been donated to Tonga, and other news suggests that, for now, Starlink services will be offered for free. But this situation will only last until another damaged submarine cable—a system that funnels the Internet between Tongatapu (the main island of the archipelagic nation) and the outlying islands—is also replaced. This task may take until the year’s end to complete, and after that, it appears that Starlink will begin charging for its services. And they are not cheap: subscriptions are $99 per month, and setting up the mountable satellite dish and router costs $499. If the standard pricing system does not change in this instance, then it may not be affordable for many in Tonga, a nation in disaster recovery mode.

That members of the private sector, including SpaceX, have been able to get a foot in the door in stricken Tonga in the wake of troubles with its state-run undersea Internet cable is not an entirely unexpected development. Nor is it inherently concerning. “But since they’re profit-making, there’s no reliability,” Kelman says. “If they’re suddenly not making a profit from Tonga, they will pull out. If they suddenly decide they’re changing from $99 a month to $300 a month, they will do it.”

High prices are not the only consideration regarding satellite Internet. The unintentionally reflective nature of SpaceX’s 2,000 or so Starlink satellites—a number that, if no legal restrictions are introduced, is set to increase exponentially in the coming years—has not only disrupted ground-based astronomy efforts. It has also added a prominent source of light pollution for certain cultures, including some of Polynesian descent, for whom stargazing plays a key role. Some consider this a desecration of a communal space. “In addressing one natural disaster on Earth, we don’t want to create another in space,” says Aparna Venkatesan, a cosmologist at the University of San Francisco, who assesses the cultural impact of satellite “megaconstellations” like Starlink.

Ultimately Tonga’s Internet connectivity troubles cannot be resolved by choosing between a state-owned undersea cable and satelliteInternet from the private sector. “You do need both,” says Jacques-Samuel Prolon, executive vice president of Kacific. A diversity of Internet options may be needed. Future-proofing places like Tonga will likely require a team effort, involving an array of partners both domestic and international, public and private. There are no individual saviors in this story.