Nonfiction

Sightseers in Space

What would a black hole look like up close?

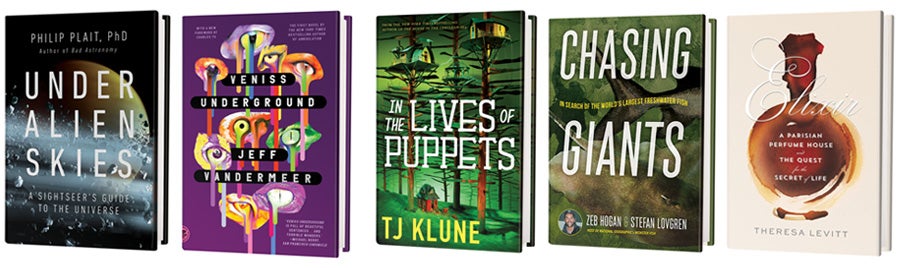

Under Alien Skies: A Sightseers Guide to the Universe

by Philip Plait

W. W. Norton, 2023 ($30)

In a nearly 30-year-old photograph of the Pillars of Creation nebula, finger-shaped spires of gas and dust reach from the heavens toward the heavens. Dark in their middles, they seem to glow around their scalloped edges: campfire smoke in still frame.

The Hubble Space Telescope took that one. Hubble's successor—the James Webb Space Telescope—recently took another portrait of the nebula, which is birthing new stars. In the JWST image, the pillars show up as defined as rock formations.

It's a fantastic view. But you may wonder, as have audiences at astronomer Philip Plait's public talks, if that's what you'd actually see were you hovering nearby. How are telescopes' views different from those of human eyes? “The question gnawed at me,” writes Plait, also known as the Bad Astronomer, in his fourth book. “What would these objects look like up close?”

Plait (who writes this magazine's monthly The Universe column) attempts to answer this question by plunking his readers in the passenger seat for a ride through the sensory realities of the cosmos. Each chapter begins with a second-person scene in which you—you!—are on a trip to some astronomical phenomenon. You begin with solar system–centric journeys: Among your first stops are the moon and Mars, where you're hit with a tornado. Then you head farther afield to comets, asteroids, Saturn and Pluto, which Plait calls “the last stop before the stars.” Jumping outward, literary explorers go on faster-than-light spaceflights to worlds with two suns and those that might exist in tightly packed spheres of stars called globular clusters. As the destinations get farther from home, the views and experiences trend ever more alien. That feeling culminates (and terminates) as you approach a black hole, where you are ultimately “crushed down to a mathematical point.”

To convincingly transport readers from couch to deep space, Plait anchors the text with familiar things to grab on to and compare from one location to the next. He explains, often using earthly analogies, why various celestial sights would look the way they do. The sky seen from the moon, for instance, is black even during the day because there's no atmosphere to scatter sunlight. On Saturn, meanwhile, it's never truly dark because the planet's reflective rings continuously send photons down to the surface. You might test the measly pull of gravity on a small, rubbly asteroid, which Plait, with characteristic wit, calls “vermin of the sky.” Always, he reminds you to look up—just as you might from your own backyard—at the stars.

For all its creative whimsy, Under Alien Skies is deeply focused on clarity, remaining evidence-based even in its imaginings. Plait cites space missions that gave scientists the data to understand these alien worlds as real places rather than cosmic abstractions. The Rosetta spacecraft, for instance, revealed that Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko—which you climb around on in the book—is shaped like a rubber duck. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter clued scientists in to a 12-mile-high dust devil, a version of which washes over you in the text.

When Plait cheekily imagines scientific details as part of the fictional exploration, the data can sometimes feel forced. He seems to be aware that it's a distraction. In a scene on a planet in the TRAPPIST-1 system, you see other potentially habitable planets orbiting close by, all circling a small red dwarf star. “One of the crewmembers starts lecturing about the physical characteristics of the planets: their distances, sizes, atmospheres,” he writes. “But all you can think of is that you're seeing alien worlds glowing in the night sky.”

There's a bit of elided wonder in that move from imagination to explanation. Plait misses a similar opportunity in largely glossing over the awe of not knowing all the astronomical things we have left to Figure out—like the 95 percent of the universe made of dark matter and energy whose nature scientists don't yet comprehend.

Fundamentally, the book is a hopeful plea for interplanetary exploration that sets up its own sequels for eons to come: “The universe is a puzzle that never ends,” Plait writes. But throughout the many-light-year journeys it contains, you're left thinking of, searching for and comparing everything with Earth. Even in the black hole at the center of the Milky Way, Plait and the reader are still thinking of home. “If you could somehow see Earth through a powerful telescope, the light from it will have been traveling for so long you'd be seeing humans living in permanent settlements for the very first time and just starting to invent pottery,” he writes.

The cosmic scale contained in that sentence doesn't just make the universe feel vast. It also shows that humans have already come a long way and that the harder-to-reach places in the universe will be waiting for us when we get there, if we ever do. —Sarah Scoles

Fiction

Mutated World

The origins of Jeff VanderMeer's creepiest creatures

Veniss Underground

by Jeff VanderMeer

MCD, 2023 ($30)

With the reissue of Veniss Underground, first published in 2003, new audiences will encounter the roots of the surrealist biohorror that best-selling author Jeff VanderMeer became known for in acclaimed novels such as Annihilation (2014).

VanderMeer's debut book, like much of his subsequent work, is a phantasmagoric thriller that explores the themes of climate disaster and humanity's selfish pursuit of control over nature. Rising sea levels have turned inland cities into detached coastal settlements, forcing the government of Veniss to build miles below Earth's surface to accommodate its citizens.

Operating on the edges of society are the Living Artists: bioengineers who practice gene manipulation to bring extinct species back to life, devise new creatures, and “improve” on animals for the benefit of humans, such as by giving meerkats opposable thumbs so they can cook and wash clothes. Part science and part perverse artwork, the practice often yields Frankenstein-like results. There's a kitten with a tongue emerging from a human ear on top of its head and a large, bioluminescent caterpillar whose body serves as a map of the underground.

The novel follows struggling artist Nicholas, his twin sister Nicola and her former lover Shadrach. When Nicholas goes to work for Quin, a powerful Living Artist whom many consider a godlike figure, he sets off a chain of events that results in Nicola's kidnapping and Shadrach's descent into the city's underground to save her. As Shadrach struggles like Dante through level after level of increasingly mutated humans and creatures, VanderMeer's talent for writing the sublime shines. There's an encounter inside a leviathan fish that has been engineered to house life without feeling the pain of its own decay.

The reprint includes four short stories and a novella, all previously published, that are also set in and around the city of Veniss. In these offshoot plots, a human settlement is under attack by Flesh Dogs that steal the faces of the people they've killed, and an artificial intelligence sows compliance through tragic stories of citizens who disobeyed their orders. It's a joy to discover here that elements in VanderMeer's later science fiction—such as the tower of living flesh in Annihilation and the bioengineered chimeras in Borne (2017)—originated in the gloom of Veniss's depths. Taken together, these works provide a chaotic and captivating window into an author's early world building. —Michael Welch

In Brief

In the Lives of Puppets

by TJ Klune

Tor, 2023 ($28.99)

Infused with warmth and playful humor, TJ Klune's latest novel both charms and challenges, tugging at our understanding of the essential self. Vic Lawson lives a peaceful but isolated life deep in the forest, a lone human raised by an android father. When Vic and his two robot companions secretly reanimate an abandoned android, they incite a crisis, sending Vic on a dangerous journey that forces him to conceal his humanity even as he discovers its complicated connections with the machines around him. Inspired by The Adventures of Pinocchio, this heartfelt saga offers a lively look at identity, free will and love. —Dana Dunham

Chasing Giants: In Search of the World's Largest Freshwater Fish

by Zeb Hogan and Stefan Lovgren

University of Nevada Press, 2023 ($29.95)

You might know Zeb Hogan as the excitable host of Monster Fish, a TV show about his quest to definitively identify the largest freshwater fish. Chasing Giants conveys the same premise in chapters instead of episodes: amid accounts of wrangling piranhas in Brazil and sawfish in Australia, Hogan and his co-author, journalist Stefan Lovgren, describe the environmental pressures endangering these targets. The final reveal is a satisfying conclusion, but it's hard to ignore the absence of voices who lent local knowledge throughout the expedition. I wanted to hear more from the hidden figures who made such a grand endeavor possible. —Sam Miller

Elixir: A Parisian Perfume House and the Quest for the Secret of Life

by Theresa Levitt

Harvard University Press, 2023 ($32.95)

In 19th-century French laboratories, scientists followed their noses in a race to discover the source of perfume's perceived vitality. Pulling from historical publications and personal writings, Theresa Levitt vividly explains why perfume—bathed in, lathered on and orally consumed—had a chokehold on Parisian life. The natural oils used to make scented products were widely considered to be the very life essence of a plant, imbued with beneficial properties that could keep death and disease at bay. Levitt traces how researchers' pursuit of the true composition of these oils laid the foundation for modern organic chemistry. —Fionna M. D. Samuels