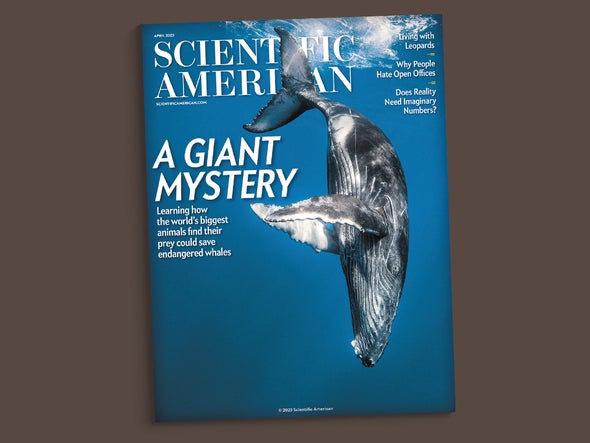

Humpback whales hunt using one of the most hilarious strategies in nature. Groups of whales swim in a circle around their prey … and blow bubbles. As the bubbles rise, they form a column that acts as a virtual net and concentrates prey. The whales swim upward in a spiral, spewing bubbles all the way, then lunge into the center of the column to grab an enormous mouthful of krill. But how do these gigantic creatures find patches of tiny krill in the first place? Scientific American's evolution and ecology senior editor Kate Wong went to Antarctica with a group of scientists studying a chemical that may give whales a scent of supper. The research, helped along by citizen scientists taking cruises to Antarctica, could help predict endangered whales' behavior and save them from ship collisions. We hope you enjoy our cover story almost as much as Kate enjoyed her reporting adventure.

It's hard to wrap your head around imaginary numbers. Unlike “real” numbers, they don't refer to physical quantities. But maybe in some sense they do? Imaginary numbers produce a negative number when multiplied by themselves. Complex numbers (which are a combination of real and imaginary numbers) have been useful in quantum theory, but many physicists assumed they were just a mathematical convenience. Physicists Marc-Olivier Renou, Antonio Acín and Miguel Navascués recently created tests of quantum theory that show imaginary numbers are necessary for certain predictions. What does it all mean for the nature of reality? They're still working on that.

We've been talking a lot at Scientific American HQ about the risks and potential rewards of artificial-intelligence programs that can generate text. This is a Very Serious Issue with implications for copyright, plagiarism, misinformation, and more—but it can also be funny. Our editors conducted an online Q&A with the AI ChatGPT and asked it why it should be regulated. (It correctly pointed out that its own “level of sophistication raises concerns about the potential for ChatGPT to be used for nefarious purposes, such as impersonating individuals or spreading misinformation.”) Computer scientist Giacomo Miceli explains how and why he created an “infinite conversation” between two AI chatbots trained to impersonate filmmaker Werner Herzog and philosopher Slavoj Žižek, who are perfect targets of a goofy but illuminating fake. (Chickens are involved.)

Have you ever worked in an open office? We're hoping to hear from readers about their own office experiences in response to Scientific American contributing editor George Musser's story. (George worked alongside many of us years ago in our first open-plan office.) Many people hate them—the lack of privacy, the noise, the germs. But they don't have to be so dehumanizing, and designers are using insights from people who are deaf or autistic to build more welcoming and productive office habitats.

Leopards have made human habitats their own. Ecologist Vidya Athreya shares her fascinating career studying leopard behavior in India, with a goal of protecting both the big cats and the people they live among. It reminds me of research on coyotes in Chicago—both types of carnivores stay in the shadows during the day and roam at night, effectively time-sharing densely populated cities. The gorgeous photos also tell the story well.

Chien-Shiung Wu was the first scientist to document entangled photons, or what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance.” It's not your fault if you haven't heard of her—she was passed over for a Nobel Prize in 1957 in one of the many discriminatory injustices in the award's history. Last year's physics prize honors research that built on her groundbreaking studies, and it's a great time to appreciate her rightful place in science. Turn to Michelle Frank's article here. If you enjoy podcasts, we publish an ongoing series called “Lost Women in Science” that is full of brilliant characters, like Wu, whose work is just now being rediscovered.