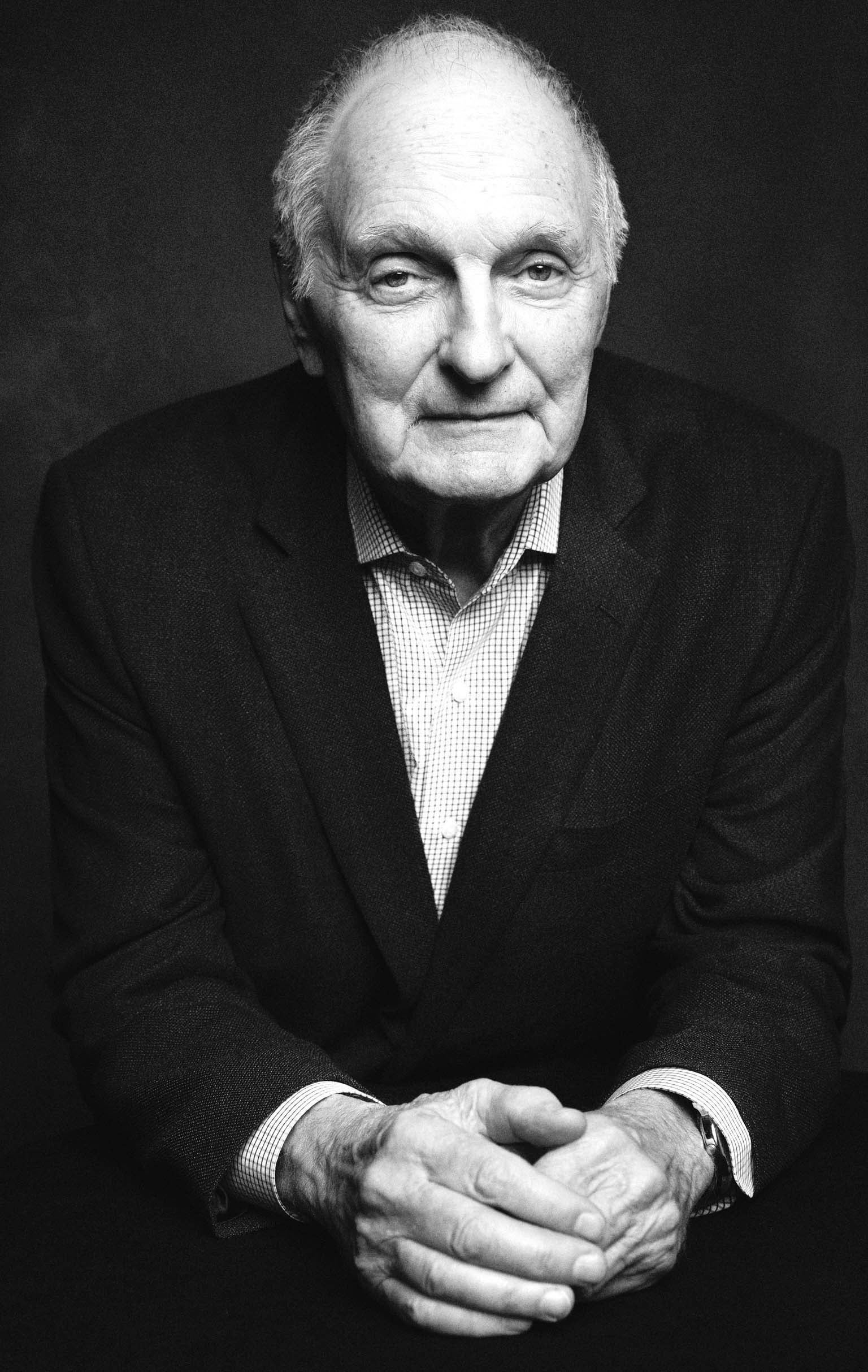

Alan Alda was running for his life. The actor, best known for his role on the television series M*A*S*H, wasn’t on a set. This threat was real—or at least it felt that way. So when he saw a bag of potatoes in front of him, he grabbed it and threw it at his attacker. Suddenly, the scene shifted. He was in his bedroom, having lurched out of sleep, and the sack of potatoes was a pillow he’d just chucked at his wife.

Acting out dreams marks a disorder that occurs during the rapid eye movement (REM) phase of sleep. Called RBD, for REM sleep behavior disorder, it affects an estimated 0.5 to 1.25 percent of the general population and is more commonly reported in older adults, particularly men. Apart from being hazardous to dreamers and their partners, RBD may foreshadow neurodegenerative disease, primarily synucleinopathies—conditions in which the protein α-synuclein (or alpha-synuclein) forms toxic clumps in the brain.

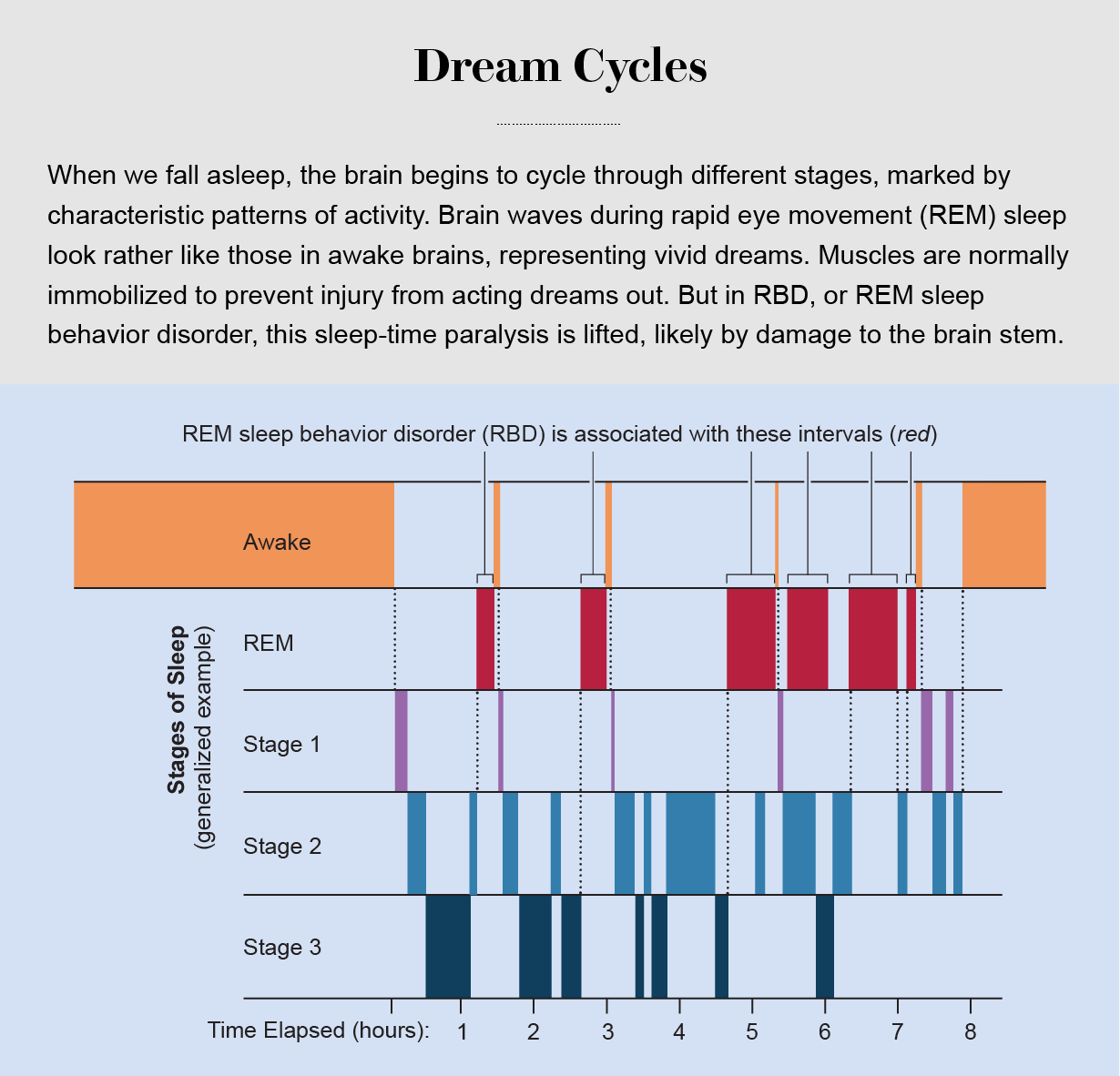

Not all nocturnal behaviors are RBD. Sleepwalking and sleep talking, which occur more often during childhood and adolescence, take place during non-REM sleep. This difference is clearly distinguishable in a sleep laboratory, where clinicians can monitor stages of sleep to see when a person moves. Nor is RBD always associated with a synucleinopathy: it can also be triggered by certain drugs such as antidepressants or caused by other underlying conditions such as narcolepsy or a brain stem tumor.

When RBD occurs in the absence of these alternative explanations, the chance of future disease is high. Some epidemiological studies suggest that enacted dreaming predicts a more than 80 percent chance of developing a neurodegenerative disease within the patient’s lifetime. It may also be the first sign of neurodegenerative disease, which on average shows up within 10 to 15 years after onset of the dream disorder.

One of the most common RBD-linked ailments is Parkinson’s disease, characterized mainly by progressive loss of motor control. Another is Lewy body dementia, in which small clusters of α-synuclein called Lewy bodies build up in the brain, disrupting movement and cognition. A third type of synucleinopathy, multiple system atrophy, interferes with both movement and involuntary functions such as digestion. RBD is one of the strongest harbingers of future synucleinopathy, more predictive than other early markers such as chronic constipation and a diminished sense of smell.

Descriptions of dream enactment by people with Parkinson’s are as old as recognition of the disease itself. In James Parkinson’s original description, “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy,” published in 1817, he wrote: “Tremulous motions of the limbs occur during sleep, and augment until they awaken the patient, and frequently with much agitation and alarm.” But despite similar reports over the next two centuries, the connection between dreams and disease remained obscure—so much so that Alda had to convince his neurologist to do a brain scan for Parkinson’s after he read about the link in a 2015 news article.

Those scans confirmed Alda’s suspicion: he had Parkinson’s. He shared his experience with the public “because I thought anybody who has any symptom, even if it’s not one of the usual ones, could get a head start on dealing with the progressive nature of the disease,” he says. “The sooner you attack it, I think, the better chance you have to hold off the symptoms.”

In recent years awareness of RBD and an understanding of how it relates to synucleinopathies have grown. Studying this link is giving researchers ideas for early intervention. These advances contribute to a growing appreciation of the so-called prodromal phase of Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative disorders—when preliminary signs appear, but a definitive diagnosis has not yet been made. Among the early clues for Parkinson’s, “RBD is special,” says Daniela Berg, a neurologist at the University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein in Germany. “It’s the strongest clinical prodromal marker we have.”

Lifting the Brake

Ray Merrell, a 66-year-old living in New Jersey, started acting out his dreams around 15 years ago. His dreamscapes became action-packed, like “something you’d watch on TV,” Merrell says. He often found himself either being chased by or chasing a person, animal or something else. In the real world, Merrell was flailing, kicking and jumping out of bed. Some of his violent nighttime behaviors injured him or his wife.

In people with RBD, the brakes that normally immobilize them during REM sleep—the stage of sleep most closely linked with dreaming—are lifted. (Dreaming also occurs in non-REM sleep, but dreams during REM are longer, more vivid and more bizarre.)

In the 1950s and 1960s French neuroscientist Michel Jouvet conducted a series of experiments that revealed just how chaotic unrestricted movements during REM sleep could be. By lesioning parts of the brain stem in cats, Jouvet inhibited the muscle paralysis that occurs in many species during REM sleep. Cats that had gone through the procedure acted normally when awake, but when asleep they became unusually active, exhibiting intermittent bursts of activity such as prowling, swatting, biting, playing and grooming. Despite this remarkably awakelike behavior, the cats remained fast asleep. Jouvet observed that the cats’ sleeping actions often were unlike their waking habits. Felines that were “always very friendly when awake,” he wrote, behaved aggressively during REM sleep.

In the late 1980s Carlos Schenck, a psychiatrist at the University of Minnesota, and his colleagues published the first case reports of RBD. Patients described having violent dreams and aggressive sleep behaviors that contrasted sharply with their nonviolent nature while awake—echoing Jouvet’s documentation of otherwise friendly felines that turned belligerent during sleep. One patient, for example, said he had a dream about a motorcyclist trying to ram him on the highway. He turned to kick the bike away—and woke to his wife saying, “What in heavens are you doing to me?” because he was “kicking the hell out of her.” Another said he dreamed of breaking a deer’s neck and woke up with his arms wrapped around his spouse’s head.

To test whether these bizarre behaviors may reflect damage to the brain stem, as in Jouvet’s cats, Schenck and his colleagues kept track of such patients to see whether they might develop a brain disease. In 1996 they reported that in a group of 29 RBD patients, all of whom were male and age 50 or older, 11 had developed neurodegenerative disease an average of 13 years after the onset of their RBD. By 2013, 21 of them, or more than 80 percent, had developed a neurodegenerative condition—the most common of which was Parkinson’s.

Subsequent studies confirmed this link. Of 1,280 patients across 24 centers around the world, 74 percent of people with RBD were diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disease within 12 years. Sometimes RBD shows up decades before other neurological symptoms, although the average lag appears to be about 10 years. When dream enactment occurs alongside other early signs of synucleinopathies, people tend to develop a neurodegenerative disease more rapidly.

Many researchers expressed skepticism about this link early on, says Bradley Boeve, a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “We would get reviewer comments back saying that this is hogwash,” he says. But the connection between RBD and synucleinopathy has become well accepted: “I think that’s pretty much gospel now.”

Some scientists suspect RBD results from an aggregation of synuclein and associated neurodegeneration in areas of the brain stem that immobilize us during REM sleep. In its normal, benign, form, the protein is involved in the functioning of neurons, but when “misfolded” into an atypical configuration, it can form toxic clumps. Autopsies have shown that more than 90 percent of people with RBD die with signs of synuclein buildup in their brains. There are no established methods to probe for synuclein clusters in the brains of living patients, but scientists have looked for the toxin in other parts of the body. Alejandro Iranzo, a neurologist at the Hospital Clinic Barcelona in Spain, and his colleagues were able to detect misfolded synuclein in the cerebrospinal fluid of 90 percent of patients with RBD.

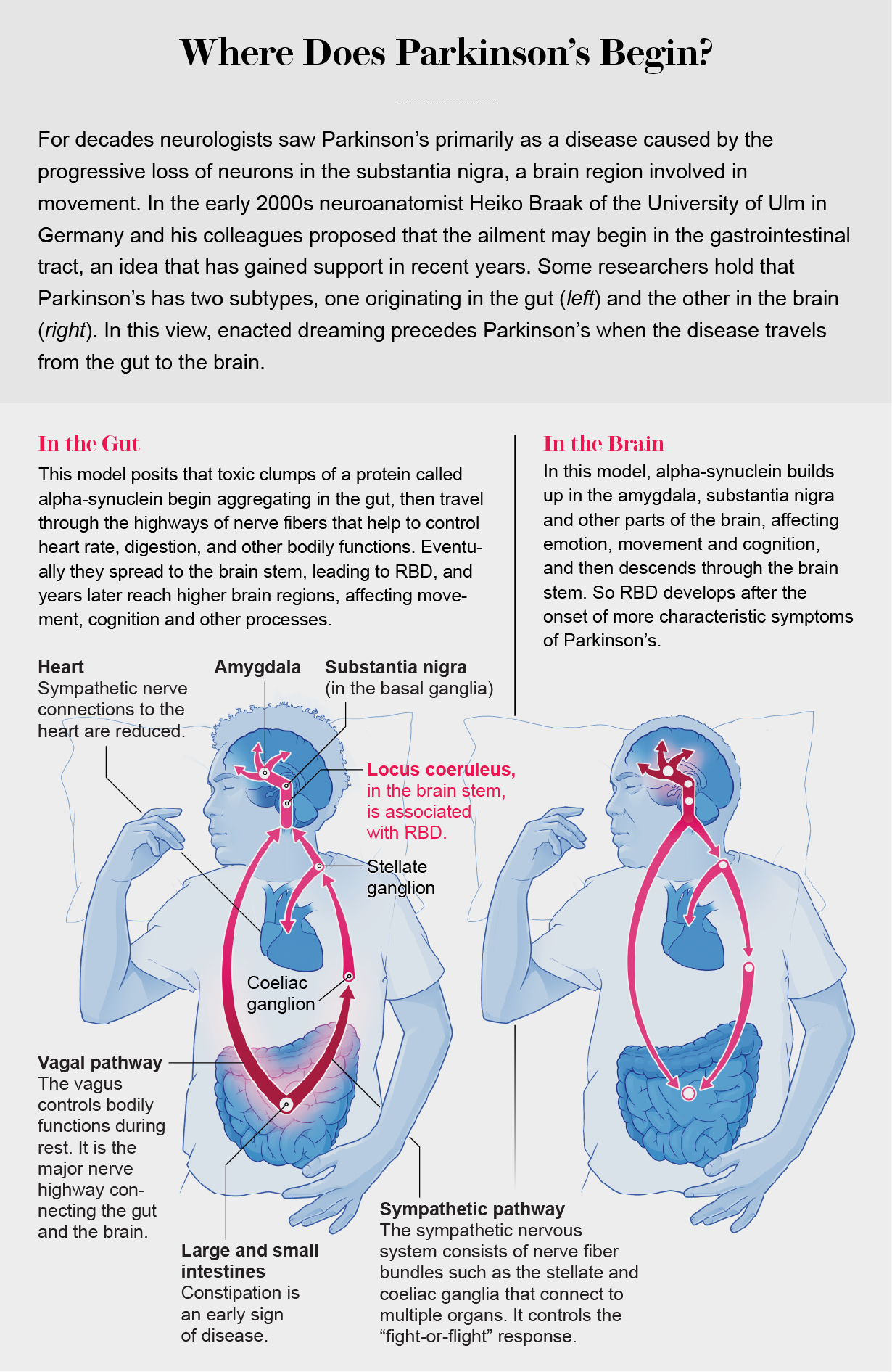

As an early manifestation of Parkinson’s and related diseases, RBD can help scientists trace the ways in which toxic synuclein spreads throughout the body and brain. Evidence is mounting that at least in some patients, pathology may begin in the gut and spread up through lower brain structures such as the brain stem to the higher regions influencing movement and cognition. One likely pathway is the vagus nerve, a bundle of nerve fibers connecting all the major organs with the brain. Alpha-synuclein clumps injected into the guts of mice can spread to the brain via the vagus—and in humans, at least one epidemiological study has shown that cutting the vagus, a procedure sometimes used to treat chronic stomach ulcers, decreases the risk for Parkinson’s later in life.

Some researchers hold that Parkinson’s has two subtypes: gut first and brain first. RBD is highly predictive of later Parkinson’s, says Per Borghammer, a professor of clinical medicine at Aarhus University in Denmark, but the converse is not true: only about a third of people with Parkinson’s get RBD before developing motor symptoms. People with RBD have gut-first Parkinson’s, Borghammer posits, and generally experience symptoms such as constipation long before motor and cognitive decline. But in the two thirds of patients who are brain first, RBD may emerge later than problems with movement—or never appear.

The Dream Theater

Does damage to the brain stem also affect the content of dreams and the actions of dreamers? Sleep researcher Isabelle Arnulf, a professor of neurology at Sorbonne University in Paris, developed a keen interest in the dream-time behaviors of her Parkinson’s patients after noticing an unusual pattern: although these people struggled with movement while awake, their spouses often reported that they had no trouble moving while asleep. One particularly memorable patient, according to Arnulf, had been dreaming of crocodiles in the sleep lab when he lifted a heavy bedside table above his head and loudly shouted, “Crocodile! Crocodile!” to an empty room. When awake, he struggled to lift objects and to speak.

Intrigued by such observations, Arnulf and her colleagues began compiling the behaviors people exhibited during REM sleep. This collection, which has grown over the past decade and a half to include hundreds of hours of footage of dream-enacting sleepers and hundreds of dream reports, has enabled Arnulf to uncover unexpected features of RBD dreams and insights into some fundamental questions about how—and why—we dream.

Merrell, Alda and many other people with RBD often have dreams in which they face danger. In one study led by Arnulf, researchers found that among people with RBD, 60 percent reported dreams involving some kind of threat, and 75 percent confronted their attacker instead of running away. People who report more frequent distressing dreams are also at greater risk of developing Parkinson’s. “It’s textbook for people with RBD to have violent dreams where they are on the defensive,” says Yo-El Ju, a professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis. But whether this is attributable to recall bias—people tending to remember more violent dreams because they are more memorable—remains an open question, she adds.

Arnulf’s group also found that a significant proportion of RBD dreams are nonviolent. In one study, 18 percent of patients flew, sang, danced, laughed, lectured or enacted other peaceable activities. In another study with 52 RBD patients, the researchers looked at subtle changes in facial expressions during sleep. Half the people smiled and a third laughed during mainly REM sleep, suggesting that RBD dreams may be more positive than previously described. Arnulf hypothesizes that violent dreams may be reported more often because aggressive behaviors are more likely to wake up the dreamer or their spouse. “I’m pretty convinced that in RBD patients, it’s just that the window is open on dreaming, but their dreams are not different from ours,” Arnulf says.

The finding that RBD patients display a range of emotions while dreaming led Arnulf to believe that what researchers learn about their dreams may apply to the broader population. Her team discovered, for example, that a small percentage of people with RBD were never able to recall their dreams despite acting out dreamlike behaviors while asleep—suggesting that self-described nondreamers may, in fact, dream.

One mystery of RBD is whether people are acting out their dreams or whether their movements are modifying their dream narratives, says Birgit Högl, a professor of neurology and sleep medicine at the Medical University of Innsbruck in Austria. As for the question that originally intrigued Arnulf—why the impaired movement characteristic of Parkinson’s seems to disappear during sleep in some patients—work by other groups has helped suggest an answer. Neurologist and psychiatrist Geert Mayer, formerly at Hephata Clinic in Germany, and his colleagues revealed in a 2015 study that the basal ganglia, movement-related structures near the base of the brain where neurodegeneration occurs in people with Parkinson’s, were silent during dream enactments in RBD patients. But other brain regions involved in producing movement, such as the motor cortex, were active.

Findings such as these suggest that in people with RBD, movement is generated through a motor circuit that bypasses the basal ganglia. “This sort of shows that whatever’s going on in Parkinson’s disease in terms of your movement doesn’t apply to you when you’re asleep,” says Ronald Postuma, a professor of neurology at McGill University. It also raises a tantalizing possibility for therapy: “What if you could mimic whatever that motor state is when a person is asleep but keep them otherwise awake?”

Early Intervention

Merrell had been enacting dreams for several years before he realized it might be a sign of a bigger problem. It began during a rough patch at work, and he had dismissed the occasional sleep outbursts as deriving from job-related stress. One evening, mid-dream, Merrell threw himself into a corner of a nightstand, breaking his skin but narrowly missing his breastbone. The close call with a very serious injury “really got me thinking that I better look into this,” Merrell says.

When Merrell was diagnosed with RBD in 2011, his doctor briefly mentioned the risk of developing other conditions down the line but “didn’t give me assurances or any other advice,” Merrell recalls. But when he began researching the condition online, he discovered many studies on RBD patients who developed a neurodegenerative disease in later life. “The more I searched,” he adds, “the more I realized, wow, this has some pretty significant implications.”

The available treatments for Parkinson’s and other synucleinopathies can currently only manage symptoms. They’re unable to slow or stop the underlying neurodegeneration. “The worst news I have to give as a sleep doctor is to tell someone that they have RBD,” Ju says.

But several new therapeutics for Parkinson’s and other synucleinopathies are being developed, and many neurologists believe early intervention could be crucial. “The Parkinson’s disease field, in particular, is full of failed treatment trials,” Ju says. “By the time people have the disease, it’s probably too late to intervene—too many cells have died.” Going back and testing these seemingly failed medications in RBD patients may prove more successful, she adds, because as a much earlier stage of disease, RBD provides a window where treatments are more likely to be effective. “A lot of people are viewing RBD as similar to high cholesterol,” Boeve says. “If you have high lipid levels, they increase your risk for heart disease and stroke. If you can alter that pathophysiological process, you can reduce the risk or delay the onset.”

Ju, Postuma and Boeve are co-leaders of the North American Prodromal Synucleinopathy (NAPS) Consortium, which launched in 2018. The NAPS investigators aim to pinpoint clinical and biological markers through various means, including brain scans, genetic screens, and tests of blood and cerebrospinal fluid. The researchers hope these markers will eventually indicate how and when a person with RBD will develop a neurodegenerative disease later in life—and which disease they will end up with. Ideally, such biomarkers would help scientists identify RBD patients for investigative therapies that target α-synuclein years before debilitating symptoms appear. The ultimate goal of NAPS, Ju says, “is essentially to prepare for clinical trials for protective treatments.”

In 2021 NAPS received a $35-million grant from the National Institutes of Health for this work, which will be carried out across eight sites in the U.S. and one in Canada. In a parallel effort, Högl, along with other researchers in Europe, is gathering a similar cohort of patients from multiple institutions across the continent for future clinical studies. Wolfgang Oertel, a neurologist at Philipps University of Marburg in Germany, who is involved in the European effort, is optimistic about the future for people with RBD. He expects that of the dozens of potentially disease-modifying Parkinson’s drugs currently in clinical trials, at least a few will be available soon. “I tell my patients, ‘You’ve come at the right moment,’” Oertel says. “You will be one of the first to get the right drugs.”

Högl has also been involved in another active area of investigation: finding ways to better characterize RBD. Working with Ambra Stefani of the Medical University of Innsbruck and other colleagues, she has been gathering measurements of muscle activity during sleep in people with RBD. They hope that this work will not only help to streamline the diagnosis of RBD but also help doctors to detect the sleep disorder even earlier, in so-called prodromal RBD, where overt dream enactments might not occur, or in people who may have RBD but exhibit only small, difficult-to-detect movements. Their work suggests that the elaborate, violent behaviors seen in RBD are “just the tip of the iceberg,” Högl says. They may occur on one night but not another. Minor muscle jerks in the hands or elsewhere, in contrast, appear to be much more frequent—and a more stable sign because they occur hundreds of times during the night, she adds.

For now there is no cure for RBD or Parkinson’s—but that doesn’t mean there is nothing patients can do. A growing body of evidence indicates that moderate to intense exercise helps to improve both motor and cognitive symptoms of Parkinson’s, and many neurologists already recommend such physical activity to their patients with RBD. “The evidence suggests that the benefits of exercise are more than just symptomatic,” says Michael Howell, a neurologist at the University of Minnesota. “It appears that this actually is helping to protect brain cells.”

Both Alda and Merrell have taken that advice to heart. In addition to medications, Alda has taken up exercise-based therapy for Parkinson’s. Merrell, too, has integrated regular physical activity into his routine, hiking for several miles every other day. He’s gotten involved in clinical research and is one of the NAPS participants. This contribution helps Merrell feel empowered—he hopes to aid the discovery of effective neuroprotective therapeutics. “Somebody always had stepped up in other illnesses or conditions that allowed for clinical trials and the therapies that we have today,” Merrell says. “I just happened to be queued up for this—and I accept that challenge.”