Every once in a while we publish a story that makes the editorial team at Scientific American melt. When we were reviewing illustrations for “The Neurobiology of Love” about pair-bonding in prairie voles, the most common response was, “Aww.” First of all, they’re so stinking cute. Unlike promiscuous species like meadow voles, they pair up for life, raise young together and cuddle for comfort. For about 50 years they’ve been the go-to animal model for studying attachment and relationships and what looks like some rudimentary version of love. Scientists Steven Phelps, Zoe Donaldson and Dev Manoli explain how we’ve learned so much about commitment from prairie voles. Some free advice: date all the meadow voles you like but marry a prairie vole.

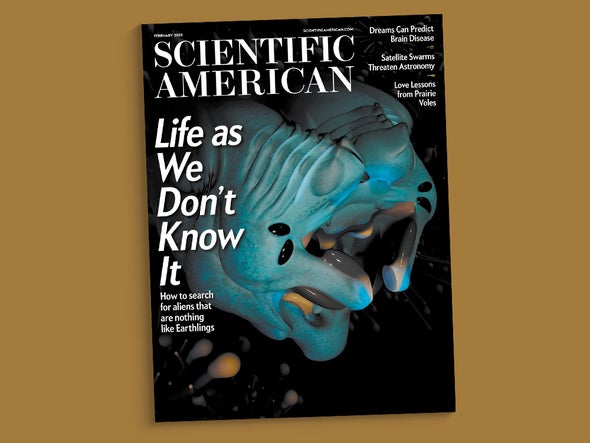

Our cover story this month is about one of the most mind-bending searches in science: the attempt to find life as we don’t know it. (Science writer Sarah Scoles proposes the acronym “LAWDKI” for this search.) How do you look for aliens that are profoundly alien to Earthlings? Scientists are figuring out how to scan for life that uses different varieties of DNA or RNA or that doesn’t use genetic sequences at all. Depending on how you define “life,” it could encompass completely different chemistry from our own or molecules that assemble themselves.

Astronomers are worried that swarms of satellites are interfering with Earth-based observatories. Increasing numbers of Starlink and other telecommunications satellites zip through low-Earth orbit and are visible with the naked eye. Until now, they’ve been exempt from environmental reviews, but a recent U.S. Government Accountability Office report suggests they could come under closer regulation. Journalist Rebecca Boyle quotes an astronomer posing a “deeper cultural question” about how much power satellite companies should have: “Should Elon Musk control what people see in the night sky?”

Actor Alan Alda is a great advocate for science communication, and he goes way back with Scientific American: he hosted a TV series with us from 1993 to 2007 called Scientific American Frontiers. Now he’s generously sharing his own experience with Parkinson’s disease to help others recognize what can be one of the earliest signs of the disease, called REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). People with the condition act out their dreams, which can be dangerous to them and their partners. Science writer Diana Kwon shows how RBD predicts neurodegenerative disease and could give patients an early start on treatments or clinical trials.

The term “positive feedback” sounds like it ought to refer to something nice, right? As climate communicator Susan Joy Hassol discusses, the language that scientists use to describe potentially catastrophic self-reinforcing cycles (that is, positive feedback) and other aspects of climate change can mislead people about the urgency of the crisis. She points out the unintended meanings of common terms and suggests much snappier and clearer alternatives. Enjoy the chalkboard that begins the article.

Some of the biggest contributors to the climate emergency are the production and use of cement and concrete, which account for about 9 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. It doesn’t have to be this way. Scientific American’s senior sustainability editor, Mark Fischetti, presents a 12-point plan for how to improve manufacturing and minimize cement’s climate impact. The wonderful graphics by illustrator and designer Nick Bockelman will make you get out your childhood dump trucks. We need all the solutions we can get.