Extreme heat was a constant in the news last summer: In July a punishing heat wave in Europe pushed temperatures across parts of the U.K. above 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius) for the first time in history. That same month was viciously hot across China, including in Shanghai—home to 26 million people—which tied its highest-ever July reading of 105.6 degrees F (40.9 degrees C). And even before the summer officially began, searing heat settled over the U.S. South in May. Amarillo, Tex., recorded its earliest day with temperatures topping 100 degrees F (37.8 degrees C), and Abilene, Tex., endured 14 straight days of 100 degrees F or higher, doubling its previous streak.

Those were just a few of the events that contributed to the Northern Hemisphere’s land areas experiencing their second-warmest June and third-warmest July on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But temperatures that make big news today may seem ho-hum—even relatively cool—within a couple of decades, as the continued burning of fossil fuels pushes baseline temperatures ever higher. Heat waves are also becoming longer and more frequent. Not every summer will be hotter than the one just before it, of course, but global warming means that the heat records set today will eventually fall down the charts. As U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo said during the July launch of Heat.gov, a government website for heat information, “The reality is, given the scientific predictions, this summer—with its oppressive and widespread heat waves—is likely to be one of the coolest summers of the rest of our lives.”

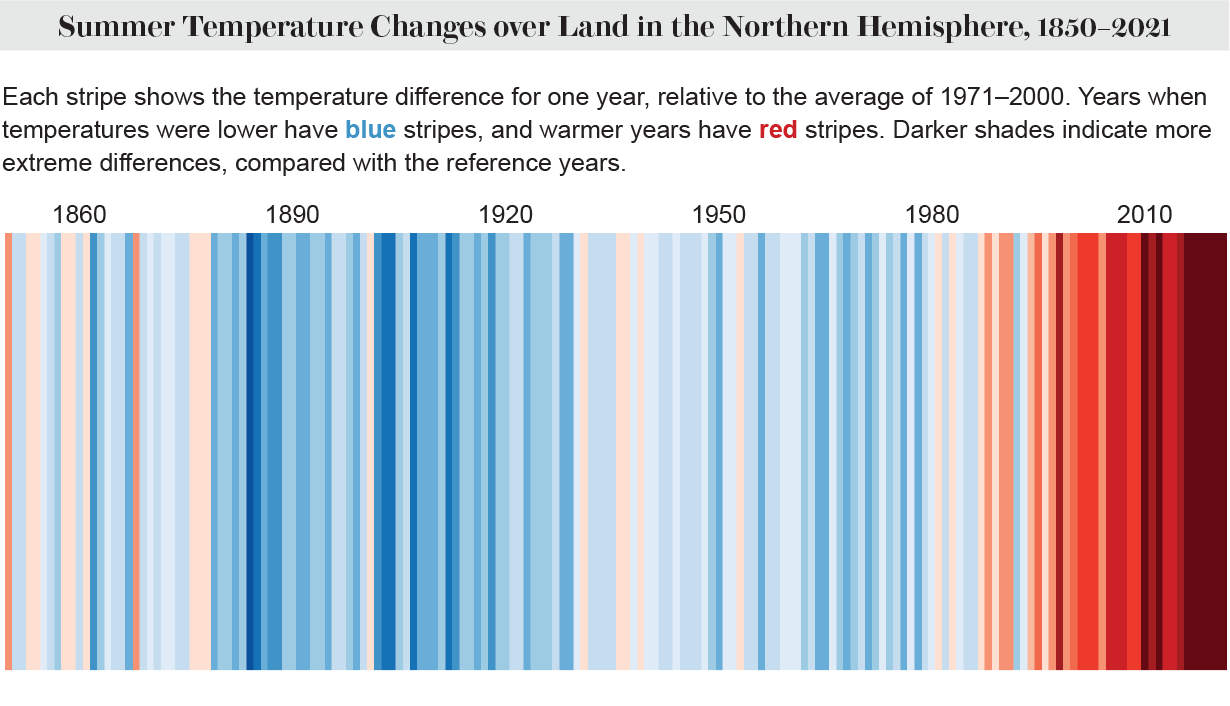

In a world without human-caused climate change, we would expect to see records set fairly randomly, following the whims of our planet’s natural variations in climate. But global warming has effectively loaded the dice, with record heat outpacing record cold. This imbalance is starkly evident in the famous “warming stripes” graphics created by climate scientist Ed Hawkins of the University of Reading in England. These graphics render each year’s average temperature as a shade of red or blue, depending on how much above or below the long-term average it is. The version on this page shows summer temperatures going back to the mid-19th century for the land areas of the Northern Hemisphere, relative to the average for 1971–2000. Although there is the odd pink or orange year scattered throughout the record, the pileup of deep red bars in recent decades immediately jumps out. Even 1998—which at the time was far and away the hottest summer (and year) on record because of an exceptionally strong El Niño event—has been far surpassed. Similarly, the 1990s were supplanted as the hottest decade by the 2000s, which were then replaced by the 2010s. The 2020s will eventually follow suit.

Natural variation of course still plays a role from year to year and month to month. For example, July 2021 was the warmest July on record for land in the Northern Hemisphere, whereas this past July came in third place. Such variations become more pronounced the more locally one looks. A relatively small area such as the U.K. can still have summers with normal temperatures in any given year. “For an individual, wherever you live, there will be colder summers than this going forward,” Hawkins says. For example, in England, which bore the brunt of last July’s heat wave in Europe, plenty of recent summers have seen temperatures at or below the long-term average. And several hot summers from the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s still rank among England’s hottest—including the standout summer of 1976, which is still a touchstone in the country’s collective memory. (That summer saw prolonged heat and drought, the latter of which also helps to increase temperatures.)

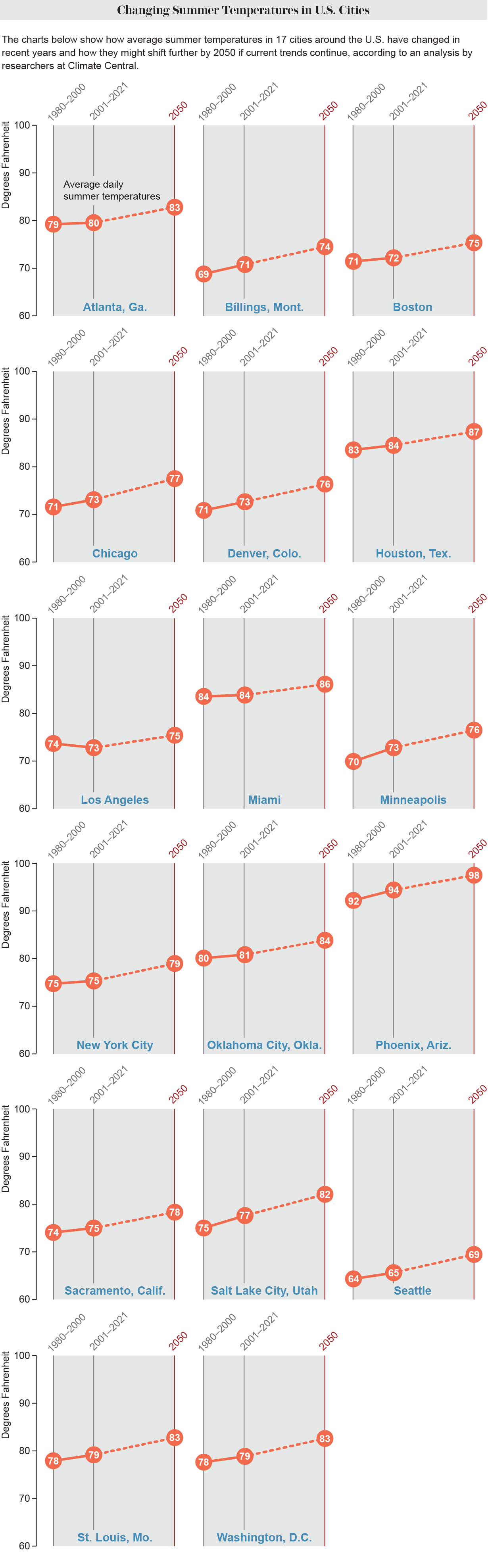

But “even if there’s a few colder years after this, it doesn’t mean climate change has gone away,” says Vikki Thompson, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol in England. The influence of climate change is still clear: average summer temperatures in England have steadily increased over recent decades, as they have everywhere. This can be seen in an analysis of past, present and projected future average summer temperatures for cities across the U.S. in the graphic above. Chicago’s average summer temperature, for instance, was 71 degrees F in the late 20th century; today it averages about 73 degrees F. In one of the higher-emissions scenarios of the future, it could average 77 degrees F. (These averages include both daytime and nighttime temperatures.)

This steadily rising baseline means that when heat waves do hit, they are worse than they would have been in the absence of climate change. An analysis of this past July’s U.K. heat wave, conducted by scientists at the World Weather Attribution consortium, found that in the absence of climate change, temperatures during such an event would have topped out around 96.8 degrees F (36 degrees C). In another decade or two, a similar event would probably lead to even higher temperatures than recorded this year.

Even heat waves that don’t set daily temperature records can be made worse by climate change. Although the southern U.S. is used to hot summers, several prolonged heat events in 2022 had highs above 100 degrees F across large areas for days at a time. Because of this, Texas recorded its hottest April–July on record and saw the average maximum temperature for July top 100 degrees F for the first time. “There were no, say, 10-day periods that are off-the-charts huge, but it’s just been relentless,” says NOAA climate scientist Derek Arndt. A recent Washington Post analysis of data from the nonprofit First Street Foundation found that long stretches of hot weather will become more frequent and last longer across the U.S., particularly in the South. Nearly half of all Americans now experience at least three consecutive days that are 100 degrees F or hotter each year, and that will increase to two thirds in the coming decades. Some parts of the South could see 70 such consecutive days.

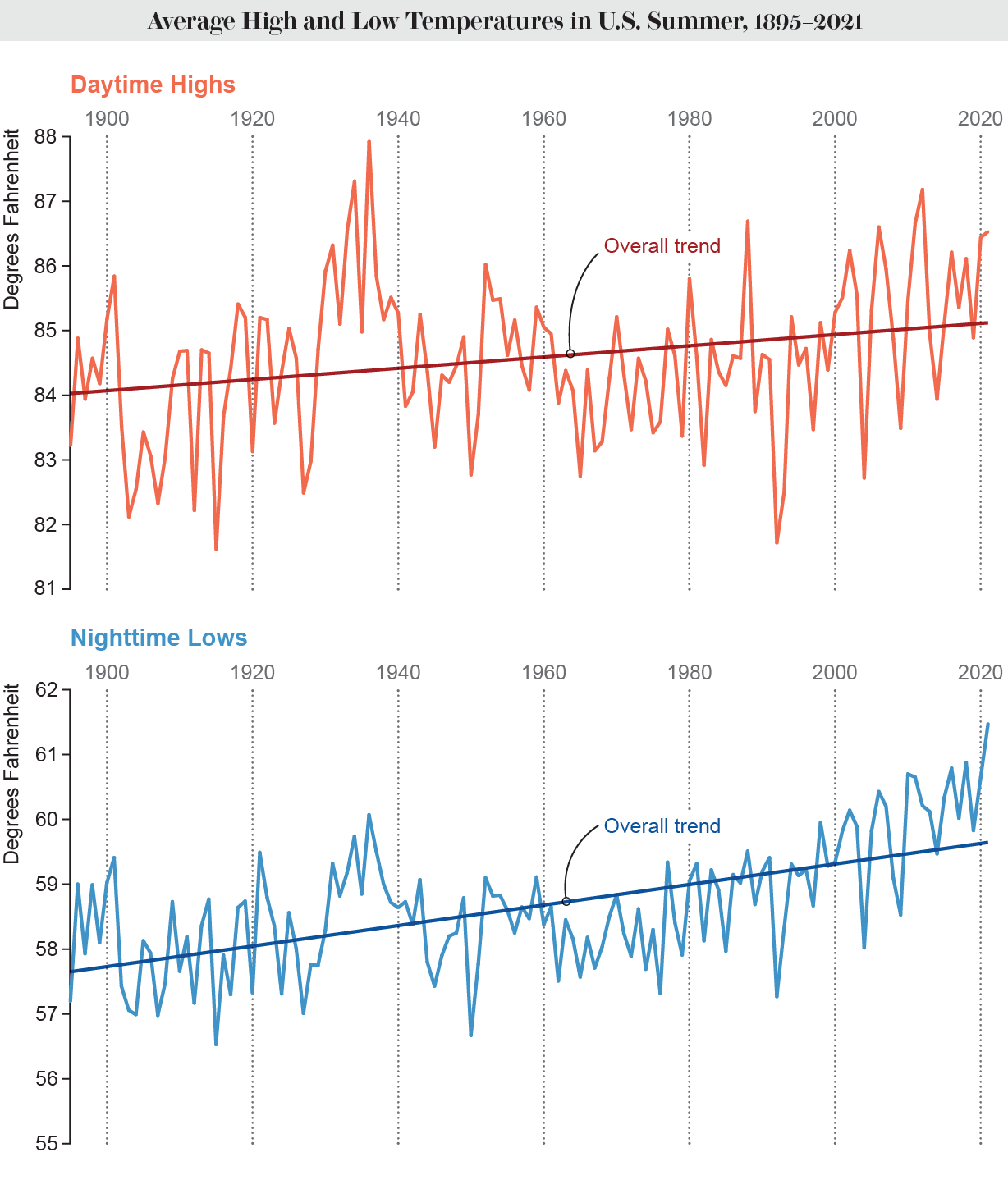

And daytime temperatures are not the only consideration. Overnight lows have been rising far faster than daytime highs in the contiguous U.S., as can be seen in the graphic on this page. Health-wise, night is when the body would usually get a break from the summer heat—so as overnight lows rise, that recovery period becomes less available. “You can’t cool down, so you’re starting the next day at that high level,” Thompson says. This can take a big toll on both physical and mental health.

The capacity of populations to cope with ever increasing and more frequent heat extremes is a key concern of the current climate emergency. Several places that are famous for cooler summers, such as the U.K. and the U.S. Pacific Northwest, have not built the infrastructure to cope with extreme heat. Many homes in these and other areas lack air-conditioning—which many may not be able to readily afford. Such constraints make it more likely that people will experience the ill health effects of heat. Even in areas accustomed to hot weather, such as Texas, prolonged extreme heat can ramp up air-conditioner use and strain the power grid.

Exactly how hot our future summers are, and how miserable we get on hot nights, is, to some degree, in our own hands. The more we curtail fossil-fuel burning now, the more we can constrain the global temperature rise that is fueling ever hotter summers. But even if we bring greenhouse gas emissions under control, we will still have to live in a hotter climate than we did in the past. That reality means helping people adapt, whether through building or retrofitting infrastructure to withstand heat, subsidizing air-conditioning or simply making sure that people have ample warning of extreme heat—and that they know how to avoid its ill health effects. “It’s our choices that make a difference,” Hawkins says.