As someone who studies the impact of misinformation on society, I often wish the young entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley who enabled communication at speed had been forced to run a 9/11 scenario with their technologies before they deployed them commercially.

One of the most iconic images from that day shows a large clustering of New Yorkers staring upward. The power of the photograph is that we know the horror they’re witnessing. It is easy to imagine that, today, almost everyone in that scene would be holding a smartphone. Some would be filming their observations and posting them to Twitter and Facebook. Powered by social media, rumors and misinformation would be rampant. Hate-filled posts aimed at the Muslim community would proliferate, the speculation and outrage boosted by algorithms responding to unprecedented levels of shares, comments and likes. Foreign agents of disinformation would amplify the division, driving wedges between communities and sowing chaos. Meanwhile those stranded on the tops of the towers would be livestreaming their final moments.

Stress-testing technology in the context of the worst moments in history might have illuminated what social scientists and propagandists have long known: that humans are wired to respond to emotional triggers and share misinformation if it reinforces existing beliefs and prejudices. Instead designers of the social platforms fervently believed that connection would drive tolerance and counteract hate. They failed to see how technology would not change who we are fundamentally—it could only map onto existing human characteristics.

Online misinformation has been around since the mid-1990s. But in 2016 several events made it broadly clear that darker forces had emerged: automation, microtargeting and coordination were fueling information campaigns designed to manipulate public opinion at scale. Journalists in the Philippines started raising flags as Rodrigo Duterte rose to power, buoyed by intensive Facebook activity. This was followed by unexpected results in the Brexit referendum in June and then the U.S. presidential election in November—all of which sparked researchers to systematically investigate the ways in which information was being used as a weapon.

During the past six years the discussion around the causes of our polluted information ecosystem has focused almost entirely on actions taken (or not taken) by the technology companies. But this fixation is too simplistic. A complex web of societal shifts is making people more susceptible to misinformation and conspiracy. Trust in institutions is falling because of political and economic upheaval, most notably through ever widening income inequality. The effects of climate change are becoming more pronounced. Global migration trends spark concern that communities will change irrevocably. The rise of automation makes people fear for their jobs and their privacy.

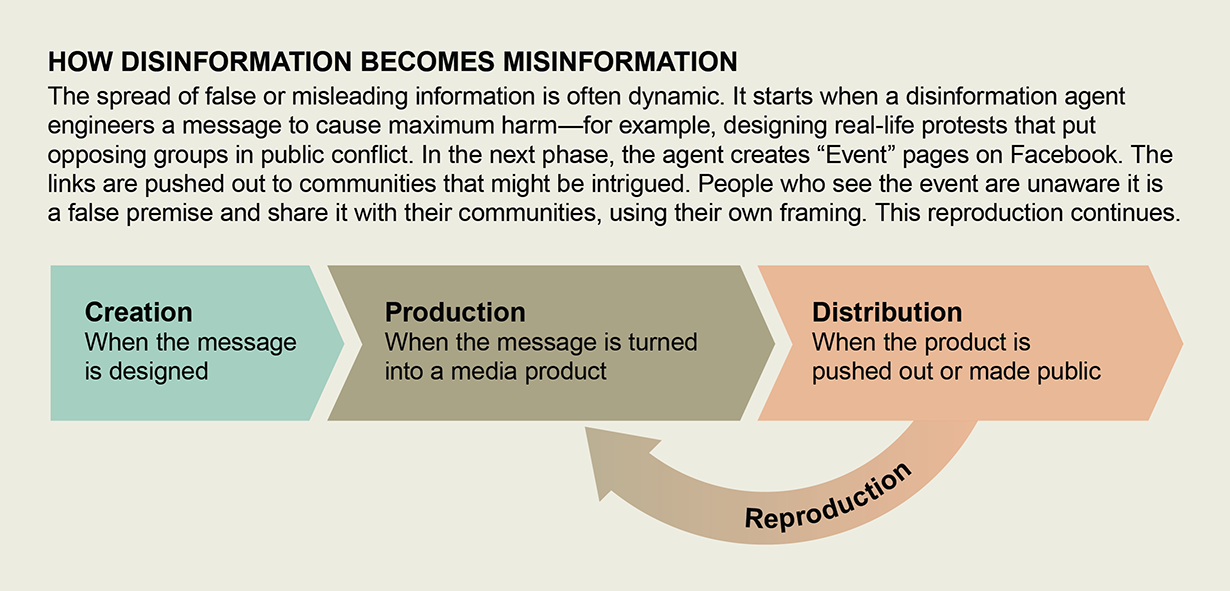

Bad actors who want to deepen existing tensions understand these societal trends, designing content that they hope will so anger or excite targeted users that the audience will become the messenger. The goal is that users will use their own social capital to reinforce and give credibility to that original message.

Most of this content is designed not to persuade people in any particular direction but to cause confusion, to overwhelm and to undermine trust in democratic institutions from the electoral system to journalism. And although much has been made about preparing the U.S. electorate for election cycles since the 2016 presidential race, misleading and conspiratorial content did not begin with that election, and it will not end anytime soon. As tools designed to manipulate and amplify content become cheaper and more accessible, it will be even easier to weaponize users as unwitting agents of disinformation.

Weaponizing Context

Generally, the language used to discuss the misinformation problem is too simplistic. Effective research and interventions require clear definitions, yet many people use the problematic phrase “fake news.” Used by politicians around the world to attack a free press, the term is dangerous. Research has shown that audiences frequently connect it with the mainstream media. It is often used as a catchall to describe things that are not the same, including lies, rumors, hoaxes, misinformation, conspiracies and propaganda, but it also papers over nuance and complexity. Much of this content does not even masquerade as news—it appears as memes, videos and social posts on Facebook and Instagram.

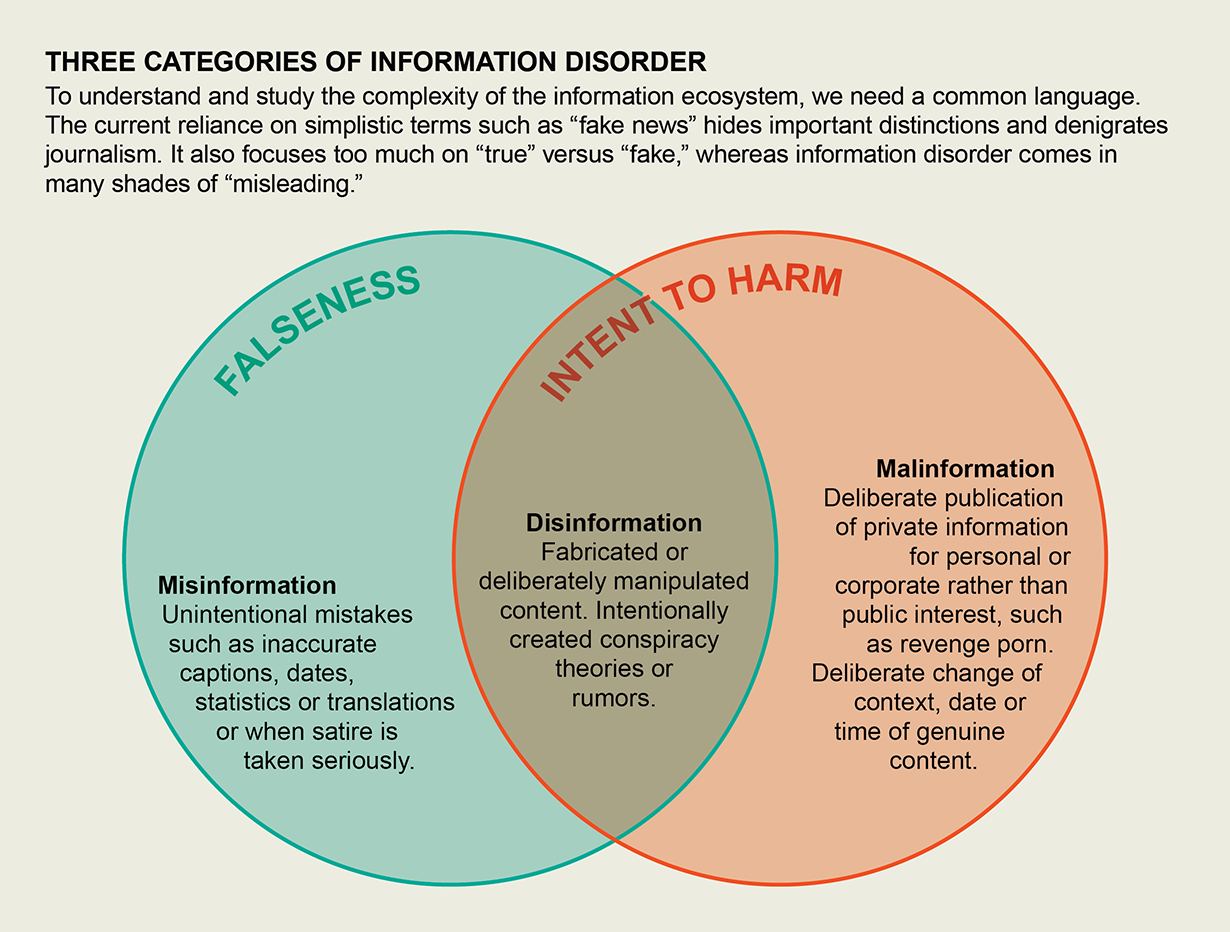

In February 2017 I created seven types of “information disorder” in an attempt to emphasize the spectrum of content being used to pollute the information ecosystem. They included, among others, satire, which is not intended to cause harm but still has the potential to fool; fabricated content, which is 100 percent false and designed to deceive and do harm; and false context, which is when genuine content is shared with false contextual information. Later that year technology journalist Hossein Derakhshan and I published a report that mapped out the differentiations among disinformation, misinformation and malinformation.

Purveyors of disinformation—content that is intentionally false and designed to cause harm—are motivated by three distinct goals: to make money; to have political influence, either foreign or domestic; and to cause trouble for the sake of it.

Those who spread misinformation—false content shared by a person who does not realize it is false or misleading—are driven by sociopsychological factors. People are performing their identities on social platforms to feel connected to others, whether the “others” are a political party, parents who do not vaccinate their children, activists who are concerned about climate change, or those who belong to a certain religion, race or ethnic group. Crucially, disinformation can turn into misinformation when people share disinformation without realizing it is false.

We added the term “malinformation” to describe genuine information that is shared with an intent to cause harm. An example of this is when Russian agents hacked into e-mails from the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign and leaked certain details to the public to damage reputations.

While monitoring misinformation in eight elections around the world between 2016 and 2020, I observed a shift in tactics and techniques. The most effective disinformation has always been that which has a kernel of truth to it, and indeed most of the content disseminated recently is not fake—it is misleading. Instead of wholly fabricated stories, influence agents are reframing genuine content and using hyperbolic headlines. The strategy involves connecting genuine content with polarizing topics or people. Because bad actors are always one step (or many steps) ahead of platform moderation, they are relabeling emotive disinformation as satire so that it will not get picked up by fact-checking processes. In these efforts, context, rather than content, is being weaponized. The result is intentional chaos.

Take, for example, the edited video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that circulated in May 2019. It was a genuine video, but an agent of disinformation slowed down the video and then posted that clip to make it seem that Pelosi was slurring her words. Just as intended, some viewers immediately began speculating that Pelosi was drunk, and the video spread on social media. Then the mainstream media picked it up, which undoubtedly made many more people aware of the video than would have originally encountered it.

Research has found that traditionally reporting on misleading content can potentially cause more harm. Our brains are wired to rely on heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to help us judge credibility. As a result, repetition and familiarity are two of the most effective mechanisms for ingraining misleading narratives, even when viewers have received contextual information explaining why they should know a narrative is not true.

Bad actors know this: In 2018 media scholar Whitney Phillips published a report for the Data & Society Research Institute that explores how those attempting to push false and misleading narratives use techniques to encourage reporters to cover their narratives. Yet another report from the Institute for the Future found that only 15 percent of U.S. journalists had been trained in how to report on misinformation more responsibly. A central challenge now for reporters and fact-checkers—and anyone with substantial reach, such as politicians and influencers—is how to untangle and debunk falsehoods such as the Pelosi video without giving the initial piece of content more oxygen.

Memes: A Misinformation Powerhouse

In January 2017 the NPR radio show This American Life interviewed a handful of Trump supporters at one of his inaugural events called the DeploraBall. These people had been heavily involved in using social media to advocate for the president. Of Trump’s surprising ascendance, one of the interviewees explained: “We memed him into power…. We directed the culture.”

The word “meme” was first used by theorist Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, to describe “a unit of cultural transmission or a unit of imitation,” an idea, behavior or style that spreads quickly throughout a culture. During the past several decades the word has been appropriated to describe a type of online content that is usually visual and takes on a particular aesthetic design, combining colorful, striking images with block text. It often refers to other cultural and media events, sometimes explicitly but mostly implicitly.

This characteristic of implicit logic—a nod and wink to shared knowledge about an event or person—is what makes memes impactful. Enthymemes are rhetorical devices where the argument is made through the absence of the premise or conclusion. Often key references (a recent news event, a statement by a political figure, an advertising campaign or a wider cultural trend) are not spelled out, forcing the viewer to connect the dots. This extra work required of the viewer is a persuasive technique because it pulls an individual into the feeling of being connected to others. If the meme is poking fun or invoking outrage at the expense of another group, those associations are reinforced even further.

The seemingly playful nature of these visual formats means that memes have not been acknowledged by much of the research and policy community as influential vehicles for disinformation, conspiracy or hate. Yet the most effective misinformation is that which will be shared, and memes tend to be much more shareable than text. The entire narrative is visible in your feed; there is no need to click on a link. A 2019 book by An Xiao Mina, Memes to Movements, outlines how memes are changing social protests and power dynamics, but this type of serious examination is relatively rare.

Indeed, of the Russian-created posts and ads on Facebook related to the 2016 election, many were memes. They focused on polarizing candidates such as Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump and on polarizing policies such as gun rights and immigration. Russian efforts often targeted groups based on race or religion, such as Black Lives Matter or Evangelical Christians. When the Facebook archive of Russian-generated memes was released, some of the commentary at the time centered on the lack of sophistication of the memes and their impact. But research has shown that when people are fearful, oversimplified narratives, conspiratorial explanation and messages that demonize others become far more effective. These memes did just enough to drive people to click the share button.

Technology platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Pinterest play a significant role in encouraging this human behavior because they are designed to be performative in nature. Slowing down to check whether content is true before sharing it is far less compelling than reinforcing to your “audience” on these platforms that you love or hate a certain policy. The business model for so many of these platforms is attached to this identity performance because it encourages you to spend more time on their sites.

Researchers have built monitoring technologies to track memes across different social platforms. But they can investigate only what they can access, and the data from visual posts on many social platforms are not made available to all researchers. Additionally, techniques for studying text such as natural-language processing are far more advanced than techniques for studying images or videos. That means the research behind solutions being rolled out is disproportionately skewed toward text-based tweets, websites or articles published via URLs, and fact-checking of claims made by politicians in speeches.

Although plenty of blame has been placed on the technology companies—and for legitimate reasons— they are also products of the commercial context in which they operate. No algorithmic tweak, update to the platforms’ content-moderation guidelines or regulatory fine will alone improve our information ecosystem at the level required.

Participating in the Solution

In a healthy information commons, people would still be free to express what they want—but information that is designed to mislead, incite hatred, reinforce polarization or cause physical harm would not be amplified by algorithms. That means it would not be allowed to trend on Twitter or in the YouTube content recommender. Nor would it be chosen to appear in Facebook feeds, Reddit searches or top Google results.

Until this amplification problem is resolved, it is precisely our willingness to share without thinking that agents of disinformation will use as a weapon. Hence, a disordered information environment requires that every person recognize how they, too, can become a vector in the information wars and develop a set of skills to navigate communication online as well as offline.

Currently conversations about public awareness tend to be focused on media literacy, often with a paternalistic framing that the public simply needs to be taught how to be smarter consumers of information. Instead online users would be better taught to develop cognitive “muscles” for emotional skepticism and trained to withstand the onslaught of content designed to trigger base fears and prejudices.

Anyone who uses websites that facilitate social interaction would do well to learn how they work—and especially how algorithms determine what users see by “prioritiz[ing] posts that spark conversations and meaningful interactions between people,” as Facebook once put it. I would also recommend that everyone try to buy an advertisement on Facebook at least once. The process of setting up a campaign helps to drive understanding of the granularity of information available. You can choose to target a subcategory of people as specific as women, aged between 32 and 42, who live in the Raleigh-Durham area of North Carolina, have preschoolers, have a graduate degree, are Jewish and like Kamala Harris. The company even permits you to test these ads in environments that allow you to fail privately. These “dark ads” let organizations target posts at certain people, but they do not sit on that organization’s main page. This makes it difficult for researchers or journalists to track what posts are being targeted at different groups of people, which is particularly concerning during elections.

Facebook events are another conduit for manipulation. One of the most alarming examples of foreign interference in a U.S. election was a protest that took place in Houston, Tex., yet was entirely orchestrated by trolls based in Russia. They had set up two Facebook pages that looked authentically American. One was named “Heart of Texas” and supported secession; it created an “event” for May 21, 2016, labeled “Stop Islamification of Texas.” The other page, “United Muslims of America,” advertised its own protest, entitled “Save Islamic Knowledge,” for the exact same time and location. The result was that two groups of people came out to protest each other, while the real creators of the protest celebrated the success at amplifying existing tensions in Houston.

Another popular tactic of disinformation agents is dubbed “astroturfing.” The term was initially connected to people who wrote fake reviews for products online or tried to make it appear that a fan community was larger than it really was. Now automated campaigns use bots or the sophisticated coordination of passionate supporters and paid trolls, or a combination of both, to make it appear that a person or policy has considerable grassroots support. They hope that if they make certain hashtags trend on Twitter, particular messaging will get picked up by the professional media, and they will be able to direct the amplification to bully specific people or organizations into silence.

Understanding how each one of us is subject to such campaigns—and might unwittingly participate in them—is a crucial first step to fighting back against those who seek to upend a sense of shared reality. Perhaps most important, though, accepting how vulnerable our society is to manufactured amplification needs to be done sensibly and calmly. Fearmongering will only fuel more conspiracy and continue to drive down trust in quality-information sources and institutions of democracy. There are no permanent solutions to weaponized narratives. Instead we need to adapt to this new normal. Just as putting on sunscreen was a habit that society developed over time and then adjusted as additional scientific research became available, building resiliency against a disordered information environment needs to be thought about in the same vein.