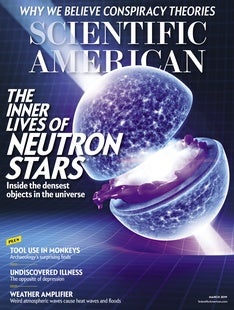

Stephan Lewandowsky was deep in denial. Nearly 10 years ago the cognitive scientist threw himself into a study of why some people refuse to accept the overwhelming evidence that the planet is warming and humans are responsible. As he delved into this climate change denialism, Lewandowsky, then at the University of Western Australia, discovered that many of the naysayers also believed in outlandish plots, such as the idea that the Apollo moon landing was a hoax created by the American government. “A lot of the discourse these people were engaging in on the Internet was totally conspiratorial,” he recalls.

Lewandowsky’s findings, published in 2013 in Psychological Science, brought these conspiracy theorists out of the woodwork. Offended by his claims, they criticized his integrity online and demanded that he be fired. (He was not, although he has since moved to the University of Bristol in England.) But as Lewandowsky waded through one irate post after another, he discovered that his critics—in response to his assertions about their conspiratorial tendencies—were actually spreading new conspiracy theories about him. These people accused him and his colleagues of faking survey responses and of conducting the research without ethical approval. When his personal website crashed, one blogger accused him of intentionally blocking critics from seeing it. None of it was true.

The irony was amusing at first, but the ranting even included a death threat, and calls and e-mails to his university became so vicious that the administrative staff who fielded them asked their managers for help. That was when Lewandowsky changed his assessment. “I quickly realized that there was nothing funny about these guys at all,” he says.

The dangerous consequences of the conspiratorial perspective—the idea that people or groups are colluding in hidden ways to produce a particular outcome—have become painfully clear. The belief that the coronavirus pandemic is an elaborate hoax designed to prevent the reelection of Donald Trump has incited some Americans to forgo important public health recommendations, costing lives. The gunman who shot and killed 11 people and injured six others in a Pittsburgh synagogue in October 2018 justified his attack by claiming that Jewish people were stealthily supporting illegal immigrants. In 2016 a conspiracy theory positing that high-ranking Democratic Party officials were part of a child sex ring involving several Washington, D.C.–area restaurants incited one believer to fire an assault weapon inside a pizzeria. Luckily no one was hurt.

The mindset is surprisingly common, although thankfully it does not often lead to gunfire. More than a quarter of the American population believes there are conspiracies “behind many things in the world,” according to a 2017 analysis of government survey data by University of Oxford and University of Liverpool researchers. The prevalence of conspiracy mongering may not be new, but today the theories are becoming more visible, says Viren Swami, a social psychologist at Anglia Ruskin University in England, who studies the phenomenon. For instance, when more than a dozen bombs were sent to prominent Democrats and Trump critics, as well as CNN, in October 2018, a number of high-profile conservatives quickly suggested that the explosives were really a “false flag,” a fake attack orchestrated by Democrats to mobilize their supporters during the U.S. midterm elections.

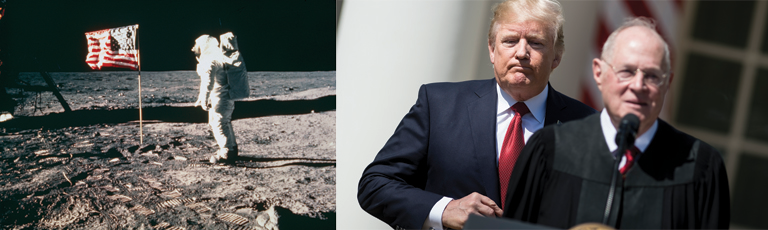

One obvious reason for the current raised profile of this kind of thinking is that the last U.S. president was a vocal conspiracy theorist. Donald Trump has suggested, among other things, that the father of Senator Ted Cruz of Texas helped to assassinate President John F. Kennedy and that Democrats funded the same migrant caravan traveling from Honduras to the U.S. that worried the Pittsburgh synagogue shooter.

But there are other factors at play, too. New research suggests that events happening worldwide are nurturing underlying emotions that make people more willing to believe in conspiracies. Experiments have revealed that feelings of anxiety make people think more conspiratorially. Such feelings, along with a sense of disenfranchisement, currently grip many Americans, according to surveys. In such situations, a conspiracy theory can provide comfort by identifying a convenient scapegoat and thereby making the world seem more straightforward and controllable. “People can assume that if these bad guys weren’t there, then everything would be fine,” Lewandowsky says. “Whereas if you don’t believe in a conspiracy theory, then you just have to say terrible things happen randomly.”

Discerning fact from fiction can be difficult, however, and some seemingly wild conspiracy ideas turn out to be true. The once scoffed-at notion that Russian nationals meddled in the 2016 presidential election is now supported by a slew of guilty pleas, evidence-based indictments and U.S. intelligence agency conclusions. So how is one to know what to believe? There, too, psychologists have been at work and have uncovered strategies that can help people distinguish plausible theories from those that are almost certainly fake—strategies that seem to become more important by the day.

The Anxiety Connection

In May 2018 the American Psychiatric Association released the results of a national survey suggesting that 39 percent of Americans felt more anxious than they did a year ago, primarily about health, safety, finances, politics and relationships. A 2017 report found that 63 percent of Americans were extremely worried about the future of the nation and that 59 percent considered that time the lowest point in U.S. history that they could remember. Such feelings span the political spectrum. A 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that the majority of both Democrats and Republicans felt that “their side” in politics had been losing in recent years on issues they found important.

Such existential crises can promote conspiratorial thinking. In a 2015 study in the Netherlands, researchers split college students into three groups. People in one group were primed to feel powerless. The scientists asked them to recall and write about a time in their lives when they felt they were not in control of the situation they were in. Those in a second group were cued in the opposite direction. They were asked to write about a time when they felt totally in control. And still others, in the third group, were asked something neutral: to describe what they had for dinner last night. Then the researchers asked all the groups how they felt about the construction of a new subway line in Amsterdam that had been plagued by problems.

Students who had been primed to feel in control were less likely than students in the other two groups to support conspiracy theories regarding the subway line, such as the belief that the city council was stealing from the subway’s budget and that it was intentionally jeopardizing residents’ safety. Other studies have uncovered similar effects. Swami and his colleagues, for instance, reported in 2016 that individuals who feel stressed are more likely than others to believe in conspiracy theories, and a 2017 study found that promoting anxiety in people also makes them more conspiracy-minded.

Feeling alienated or unwanted also seems to make conspiratorial thinking more attractive. In 2017 Princeton University psychologists set up an experiment with trios of people. The researchers asked all participants to write two paragraphs describing themselves and then told them that their descriptions would be shared with the other two in their group, who would use that information to decide if they would work with the person in the future. After telling some subjects that they had been accepted by their group and others that they had been rejected, the researchers evaluated the subjects’ thoughts on various conspiracy-related scenarios. The “rejected” participants, feeling alienated, were more likely than the others to think the scenarios involved a coordinated conspiracy.

It is not just personal crises that encourage individuals to form conspiratorial suspicions. Collective social setbacks do so as well. In a 2018 study, researchers at the University of Minnesota and Lehigh University surveyed more than 3,000 Americans. They found that participants who felt that American values were eroding were more likely than others to agree with conspiratorial statements, such as that “many major events have behind them the actions of a small group of influential people.” Joseph Uscinski, a political scientist at the University of Miami, and his colleagues have shown that people who dislike the political party in power think more conspiratorially than those who support the controlling party. In the U.S., political liberals put forth a number of unproved conjectures as conservatives ascended to control the government in recent years. These include the charge that the White House coerced Anthony Kennedy to retire from the U.S. Supreme Court and the allegation that Russian president Vladimir Putin is blackmailing Trump with a video of him watching prostitutes urinate on a Moscow hotel bed.

When feelings of personal alienation or anxiety are combined with a sense that society is in jeopardy, people experience a kind of conspiratorial double whammy. In a study conducted in 2009, near the start of the U.S.’s Great Recession, Daniel Sullivan, a psychologist now at the University of Arizona, and his colleagues told one group that parts of their lives were largely out of their control because they could be exposed to a natural disaster or some other catastrophe and told another group that things were under their control. Then participants were asked to read essays that argued that the government was handling the economic crisis either well or poorly. Those cued about uncontrolled life situations and told their government was doing a bad job were the most likely to think that negative events in their lives would be instigated by enemies rather than random chance, which is a conspiratorial hallmark.

Although humans seek solace in conspiracy theories, they rarely find it. “They’re appealing but not necessarily satisfying,” says Daniel Jolley, a psychologist at the University of Nottingham in England. For one thing, conspiratorial thinking can incite individuals to behave in a way that increases their sense of powerlessness, making them feel even worse. A 2014 study co-authored by Jolley found that people who are presented with conspiracy theories about climate change—scientists are just chasing grant money, for instance—are less likely to plan to vote. And a 2017 study reported that believing in work-related conspiracies—such as the idea that managers make decisions to protect their own interests—causes individuals to feel less committed to their job. “It can snowball and become a pretty vicious, nasty cycle of inaction and negative behavior,” says Karen Douglas, a social psychologist at the University of Kent in England and a co-author of the paper on work-related conspiracies.

The negative and alienating beliefs can also promote dangerous behaviors in some, as with the Pittsburgh shootings and the pizzeria attack. But the theories need not involve weapons to inflict harm. People who believe vaccine conspiracy theories, for example, say they are less inclined to vaccinate their kids, which creates pockets of infectious disease that put entire communities at risk.

Telling Fact from Fiction

It may be possible to quell conspiracy ideation, at least to some degree. One long-standing question has been whether it is a good idea to counter conspiracy theories with logic and evidence. Some older research has pointed to a “backfire effect”—the idea that refuting misinformation can just make individuals dig their heels in deeper. “If you think there are powerful forces trying to conspire and cover [things] up, when you’re given what you see as a cover story, it only shows you how right you are,” Uscinski says.

But other research suggests that this putative effect is, in fact, rare. A 2016 paper reported that when scientists refuted a conspiracy theory by pointing out its logical inconsistencies, it became less enchanting to people. And in a study published online in 2018 in Political Behavior, researchers recruited more than 10,000 people and presented them with corrections to various claims made by political figures. The authors concluded that “evidence of factual backfire is far more tenuous than prior research suggests.” In a review article, the researchers who first described the backfire effect said that it may arise most often when people are being challenged over ideas that define their worldview or sense of self. Finding ways to counter conspiracy theories without challenging a person’s identity may therefore be an effective strategy.

Encouraging analytic thinking may also help. In a 2014 study published in Cognition, Swami and his colleagues recruited 112 people for an experiment. First, they had everyone fill out a questionnaire that evaluated how strongly they believed in various conspiracy theories. A few weeks later the subjects came back in, and the researchers split them into two groups. One group completed a task that included unscrambling words in sentences containing words such as “analyze” and “rational,” which primed them to think more analytically. The second group completed a neutral task.

Then the researchers readministered the conspiracy theory test to the two groups. Although the groups had been no different in terms of conspiratorial thinking at the beginning of the experiment, the subjects who had been incited to think analytically became less conspiratorial. Thus, by giving people “the tools and the skills to analyze data and to look at data critically and objectively,” we might be able to suppress conspiratorial thinking, Swami says.

Analytical thinking can also help discern implausible theories from ones that, crazy as they sound, are supported by evidence. Karen Murphy, an educational psychologist at Pennsylvania State University, suggests that individuals who want to improve their analytic thinking skills should ask three key questions when interpreting conspiracy claims. One: What is your evidence? Two: What is your source for that evidence? Three: What is the reasoning that links your evidence back to the claim? Sources of evidence need to be accurate, credible and relevant. For instance, “you shouldn’t take advice from your mom about whether the yellow color under your fingernails is a bad sign,” Murphy says—that kind of information should come from someone who has expertise on the topic, such as a physician.

In addition, false conspiracy theories have several hallmarks, Lewandowsky says. Three of them are particularly noticeable. First, the theories include contradictions. For example, some deniers of climate change argue that there is no scientific consensus on the issue while framing themselves as heroes pushing back against established consensus. Both cannot be true. A second telltale sign is when a contention is based on shaky assumptions. Trump, for instance, claimed that millions of illegal immigrants cast ballots in the 2016 presidential election and were the reason he lost the popular vote. Beyond the complete lack of evidence for such voting, his assumption was that multitudes of such votes—if they existed—would have been for his Democratic opponent. Yet past polls of unauthorized Hispanic immigrants suggest that many of them would have voted for a Republican candidate over a Democratic one.

A third sign that a claim is a far-fetched theory, rather than an actual conspiracy, is that those who support it interpret evidence against their theory as evidence for it. When the van of the convicted mail bomber Cesar Sayoc was found in Florida plastered with Trump stickers, for instance, some individuals said this helped to prove that Democrats were really behind the bombs. “If anyone thinks this is what a real conservative’s van looks like, you are being willfully ignorant. Cesar Sayoc is clearly just a fall guy for this obvious false flag,” one person posted on Twitter.

Conspiracy theories are a human reaction to confusing times. “We’re all just trying to understand the world and what’s happening in it,” says Rob Brotherton, a psychologist at Barnard College and author of Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe in Conspiracy Theories (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2015). But real harm can come from such thinking, especially when believers engage in violence as a show of support. If we look out for suspicious signatures and ask thoughtful questions about the stories we encounter, it is still possible to separate truth from lies. It may not always be an easy task, but it is a crucial one for all of us.