Hidden inside a rocky outcrop near a flock of grazing sheep, a miniature world of marine creatures—whose guts, eyes and even brains remain visible after some 462 million years—has been uncovered by researchers.

Paleontologists Lucy Muir and Joseph Botting discovered the pint-sized fossil trove within walking distance from their home at Castle Bank Quarry in Central Wales. At the time the aquatic creatures were alive, this area was a rocky sea shelf fringing a volcanic island.

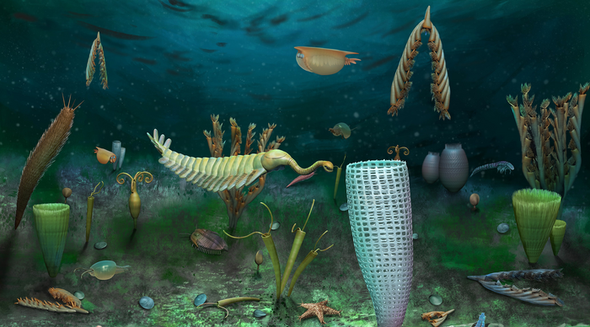

In a new study published online on May 1 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, the duo and their colleagues in England, Sweden and China describe the site’s ancient inhabitants, most of which are just a couple of millimeters long and include nozzle-mouthed worms, horseshoe crabs, starfish and early barnacles. Also in the fossil trove are tiny enigmatic holdovers from the preceding Cambrian explosion, a period that started about 540 million years ago, when a burst of diverse life-forms emerged.

The paleontologist couple initially discovered the deposit in 2013, when they spotted sponge fossils in a small quarry surrounded by sheep pasture. For years Muir and Botting, who are honorary research fellows at Amgueddfa Cymru–National Museum Wales, returned to the site to look for more fossils. But they failed to find traces of anything other than sponges.

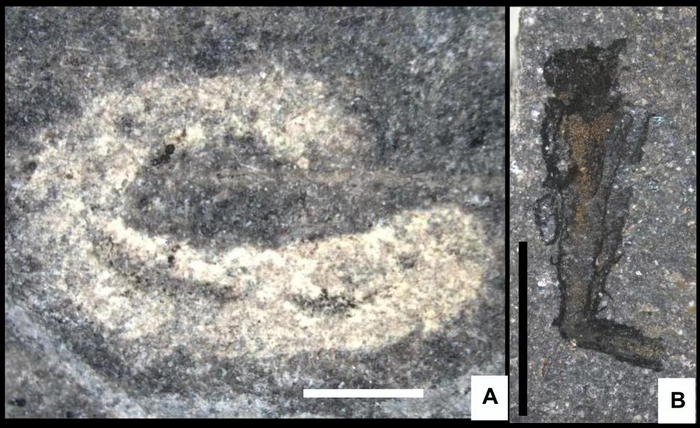

During the COVID lockdown in 2020, they began describing the local suite of sponges as a pandemic project. One day Botting headed down to the quarry to search for more sponges. “And of course, that is the day that I first found a little tube with tentacles sticking out,” he recalls.

That fossil, which is only 3.5 mm tall and resembles a spindly alien spacecraft, looked unlike anything either paleontologist had ever seen. They quickly realized they were just scratching the site’s surface. Within a two-meter-thick band of rock, Botting and Muir found traces of a thriving ecosystem. Like a developing photograph, the fossils became apparent several seconds after the paleontologists cracked open the rocks. “You split them open, and after 30 seconds, they just magically appear,” Botting says.

Over several months the paleontologists discovered the fossils of around 170 different species that likely inhabited the rocky slope along a subsiding volcano. In addition to sponges and worms were trilobites, arthropods sporting grasping appendages and a six-legged animal that looked remarkably similar to a primitive insect that did not appear until millions of years later. There was also an animal reminiscent of Opabinia, a weird wonder of the Cambrian that had five eyes and a trunklike proboscis. Many of these evolutionary oddballs were delicately etched into the ash-colored stone, where soft-body features such as gills, digestive tracts, optic nerves and neural tissue—which rarely fossilize—were easily visible.

The exquisite preservation of Castle Bank’s fossils resembles that uncovered from the Burgess Shale, the iconic, 500-million-year-old Cambrian deposit in the Canadian Rockies that has yielded the remains of some of the oldest complex animals on Earth. Researchers have found similarly stunning Cambrian fossil sites around the world.

But beautifully maintained animals are much rarer in the succeeding Ordovician period. According to Alycia Stigall, a paleontologist at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, this is potentially because of a change in ocean chemistry during the Ordovician or a rise in burrowing organisms that exposed the remains of other animals to decay. Without these remnants, scientists know little about the majority of soft-bodied organisms that lived in the aftermath of the Cambrian explosion. “Today nonbiomineralizing organisms make up [around] 70 percent of all animals,” she says, referring to soft-bodied creatures. “Snapshots into the history of nonbiomineralizing animals like the Castle Bank fauna is incredibly important for developing a fuller understanding of the history of life,” adds Stigall, who was not involved in the new study.

The newfound fossils also offer an unparalleled glimpse into a dynamic chapter of evolution called the great Ordovician biodiversification event. “This is when life started to get really interesting,” Muir says. “As animals diversified, ecosystems became a lot more complicated.” While animal sizes stayed constant throughout the Cambrian, some ecosystems seemed to downsize during the Ordovician. Castle Bank’s fossils are generally small. Most of them measure between 1 and 5 mm.

Such shrinkage would usually be chalked up to a fossilization quirk where large-bodied organisms were washed away before they could be buried. But Botting and Muir think Castle Bank truly represents an ecosystem dominated by small life-forms. The stunning preservation of these fossils’ soft tissues reveals that the entire ecosystem was likely buried instantly, perhaps by a sudden rockslide, and this prevented decay and kept scavengers at bay. If larger creatures were milling around the ecosystem, they would have been buried alive as well. All the site’s trilobites are also juveniles, suggesting that this could have been a nursery. The paleontologists believe that the site’s relatively larger sponges and algae, which measure a couple of centimeters, offered the perfect habitat for these tiny creatures.

Though a miniscule realm of sea creatures may seem odd, Muir stresses that they remain a staple of ocean environments. “Most animals are small, and big animals are the exception,” Muir says. “It’s just that they’re harder to see.”

The researchers are still working to describe dozens of Castle Bank fossils in greater detail, including the tube-dwelling tentacled creature and the animal that resembles a possible marine precursor to insects. Like it was during the lockdown, their house is currently overflowing with fossils from the site. “Our spare room is so full, you can't sleep on the bed,” Botting says.